Fighter for the republic despite his blue blood, his hand threw a bomb against Napoleon III; saved from the death sentence by his powerful English father-in-law, he ended up in forced labor on Devil’s Island from which he managed to escape like not even Papillon in the novel and film fiction; wearing the blue uniform of the Union army he became an officer during the Civil War and ended up in Colonel Custer’s legendary 7th Cavalry, surviving the epochal disaster of Little Big Horn.

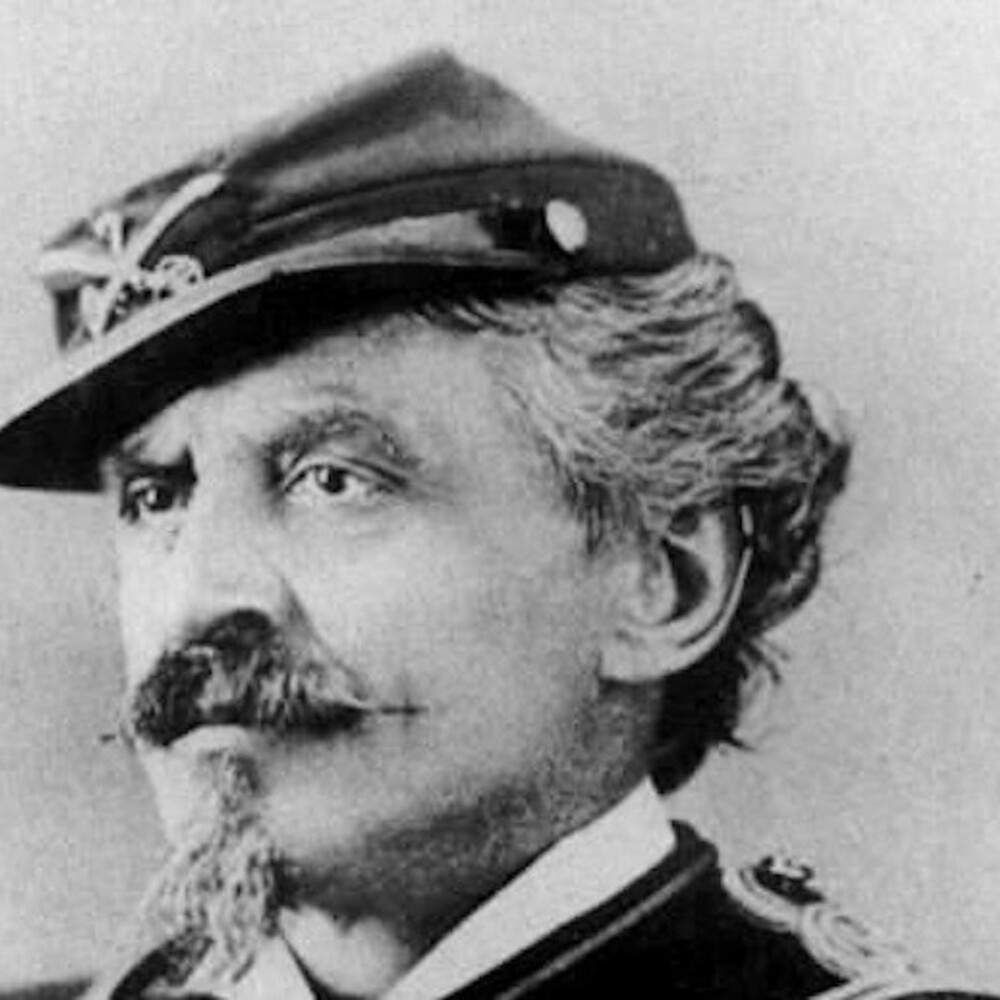

Even too much for just one life, but in reality there is incredibly much more to his. Carlo Camillo Di Rudio in the United States is known as Charles DeRudio. Italian from Belluno, born in 1832 to an aristocratic family (father Ettore Placido count, mother Elisabetta countess), from a young age he was initiated into a career in arms under the flag of the Emperor of Austria.

A bomb against the emperor and the escape from Devil’s Island in Cayenne

At just sixteen years old, in 1848, he took part in the Five Days of Milan, but against the Austrians, and together with his brother Achille, a cadet like him, he was credited with killing a Croatian soldier responsible for violence against two women. Despite his blue blood, he lights up for Mazzini’s ideals. He then puts his sword at the service of the Republic of Venice, where his brother dies killed by cholera, then of the Roman Republic, in one of the most beautiful pages of the Risorgimento, alongside Giuseppe Garibaldi.

He was under fire by the Austrian police and fled to France in 1851, where he also disguised himself as a priest, then returned to his homeland and in 1857 tried to reach the United States but an unfortunate shipwreck kept him in restless Europe where everyone seemed eager to get their hands on him for his conspiracy activity which had even put his family, who had been arrested, under fire. He arrives in England where he meets fifteen-year-old Eliza Booth and marries her.

He seems to have put his head in order, despite the economic difficulties, but it doesn’t last long. The revolutionary spirit burns in his soul. With the coup d’état of 1852, Charles Louis Napoleon Bonaparte had himself proclaimed emperor and all his liberal and republican spirit seemed to have been transfigured in an authoritarian sense as a symbol of that power that Count Di Rudio had already opposed in Rome with Mazzini.

Having escaped the death sentence, he fled to British Guiana

When Felice Orsini planned an attack in Paris to eliminate the new expression of oppression, the Italian exile said he was ready to do his part. One of the three bombs aimed at the emperor in rue Montpellier on the evening of 14 January 1858 was thrown by him. Napoleon III escaped unharmed, but eight were killed and 156 were injured. The Italian attackers were immediately arrested and tried.

Orsini and Giovanni Andrea Pieri were sentenced to death and guillotined on March 31, while Di Rudio, thanks to the high-ranking connections of his father-in-law and the English intercessions, escaped capital punishment but not the life sentence to be served on Devil’s Island, the terrible penal colony of Cayenne, in Guyana.

Mazzini’s letter of recommendation and his career as an officer in the USA

Once deported to Guyana, Carlo Di Rudio’s first thought was to leave as soon as possible, also because on top of everything he had to face the hostility of the other French prisoners. The first time went badly, but in 1859 the group escape was crowned with success. Once in British Guiana Di Rudio was safe, and managed to reunite with his family in London the following year without too many problems.

But there was absolutely no question of returning to Italy: he was wanted by the French and Austrian police who had also spread the news that he was a spy. Giuseppe Mazzini wrote a letter of recommendation for him which had some weight in the United States. And then the count moved to the New World with his whole family. In New York he changed his name and became Charles DeRudio, enlisted in the Union army in 1861 with the infantry insignia of the 79th New York Volunteers and soon promoted to second lieutenant. No one knew anything about his checkered past, except some members of the Republican Party.

And so in 1869 DeRudio served in the ranks of the 7th Cavalry Regiment under the orders of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, already a general during the Civil War and then forced down in rank due to the drastic reduction of the army’s cadres.

Witness the massacre and ritual scalping of soldiers by squaws

On June 25, 1876, DeRudio had been added to Captain Marcus Reno’s company at the last moment, when Custer fell into the trap of the Sioux and Cheyenne of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse at Little Big Horn. Reno will later be accused of negligent conduct for not immediately running to help his commander’s columns torn to pieces by the Indians in one of the most searing defeats of the American army, and certainly the best known.

But he will emerge clean from the investigation, and so will Lieutenant DeRudio, whose correctness of actions and also his value in the field were confirmed in the trial. At Little Big Horn his horse had been killed in the fighting, his unit had been decimated and he had managed to save himself in a thicket from where he had witnessed the destruction of the bodies of his fallen comrades by the squaws who scalped them, as per the custom of the redskins.

For this reason, as an eyewitness, he will be heard by the commission that was supposed to shed light on the defeat and the massacre. His name was everywhere in the newspapers and his popularity was widespread. Another Italian who was saved from the massacre was the trumpeter John Martin, or rather Garibaldi’s Giovanni Martini, sent as a messenger by Custer to request the sending of reinforcements. In total, there were about ten Italians in the 7th Cavalry wearing blue jackets, all of them in the troop. Most of them were former Garibaldians.

A life summed up in the names of his three daughters: Italy, Rome and America

DeRudio will have time to participate in the last phase of the Indian wars and in 1895 he will retire at the age of 64 with full honors and the rank of captain, which will then be raised to that of major. He died in California, in Pasadena, on November 1, 1910, and was buried in San Francisco. Her life experiences and the ideals that had animated her were exemplified by the names chosen for the three daughters she had with Eliza, who were named Italy, Rome and America.