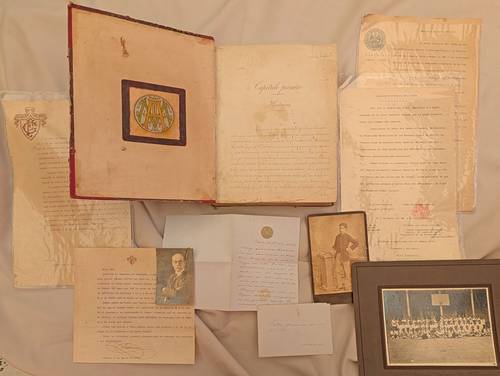

The National Library of Mexico (BNM) is in the process of acquiring a set of documents, including a little-known photograph of the writer and journalist Ignacio Manuel Altamirano (1834-1893), taken in his youth, and a letter from the diplomat also addressed to the cultural manager Rosario de la Peña (1847-1924).

The letter is signed by Altamirano himself dated October 22, 1889, in Paris, France. “It (the document) is very important; here he had already left for Europe. It also has his monogram. You can see that (the sheet on which it was written) is from his stationery store,” explained Miguel Ángel Castro Medina, a specialist at the Bibliographic Research Institute, in an interview with The Day, who also read a fragment of the letter in which the author narrates his trip: “Dear Rosario: On my path…”

The expert detailed its historical relevance, insisting that it is a very personal text, in which aspects of the author’s life are appreciated. “Altamirano became ill, left the government and died in Europe, in San Remo, Italy.” The document reads: “My old diabetes reappeared in its acute period,” a fact that Castro Medina considered “very important.”

The other materials

In addition to the mentioned objects, the package – which is already in the BNM facilities – includes letters, documents and photographs of the novelist and playwright Federico Gamboa (1864-1939). There is also the manuscript of hydrangea, alleged unpublished novel by Ignacio Manuel Altamirano.

According to Castro Medina, it is not possible to ensure that it is his authorship, since it is necessary to carry out an exhaustive investigation. “I looked in a book we have on monographic works from the 19th century, to see if by chance a Hydrangea. And no, we didn’t find it, but it could appear with another title.”

The specimen has a from books of Altamirano “which could well have been posted later by someone. All these things must be investigated,” he specified. He also commented that, at first glance, it seems that some pages were torn from the beginning. “You have to study that, because maybe you had the credits and a degree there.”

He stressed that “when a writer as important as Altamirano leaves a work unfinished, there is news. For example, for many years I have been looking for a draft or a version of The shadow of Medrano, by Micrós (pseudonym of Ángel de Campo). “I know that he published it because there are other writers, like Victoriano Salado Álvarez and others who talk about having had that work in their hands, in their diaries and everything.”

The study

Salvador Calva Carrasco, doctor in Latin American literature and professor at the Metropolitan Autonomous University (UAM), told this medium that the BNM must carry out a comprehensive study that ranges from the analysis of paper and calligraphy, to the identification of paratextual data – such as marks and dates – that may provide clues about its origin.

“You must also review not only the materials, but the text itself. The words used, the metaphors, the resources, the rhetorical figures in general”, in order to determine if the text corresponds to Altamirano’s style, to the topics discussed in his time and to the vocabulary of the time.

For his part, Miguel Ángel Castro warned that the specimen cannot be linked to Altamirano “until conclusive evidence appears” during the investigation process. Likewise, one of the specialist’s first impressions is that the material could be a copy, since in a manuscript “you can see the erasures, the changes,” made by the author during writing, something absent in the neatness of the manuscript. Hydrangea.

The discovery

The lot containing these materials was purchased on April 2 by staff at the Valis Libros Raros used bookstore from Juan Carlos de León Romero – grandson of Darío Romero León, former mayor of Cabo Corrientes, Jalisco (1983-1985) – who kept the documents in his library until his death.

Around May, Sebastián Alberto Contreras Zúñiga, founder of Valis Libros Raros, offered the archive to the BNM. During the first review of the package, Castro Medina recommended to the library’s acquisitions department to buy it, because, in his opinion, “it is worth it”, since the letters are signed by both authors, it includes an authentic photograph of the author of El Zarco and an “unknown” manuscript that may be the subject of research.

However, the analysis could continue indefinitely, especially because the material must not yet be manipulated by researchers from the institution, given that the acquisition process has not yet concluded.

Salvador Calva celebrated the incorporation of the documents by the BNM, because, although “it will probably take a while to ensure that (the manuscript) is from Altamirano, the truth is that we can be sure that the institution has sufficient resources or contacts to turn to other figures, whether they are researchers or institutions, in order for them to review it.”