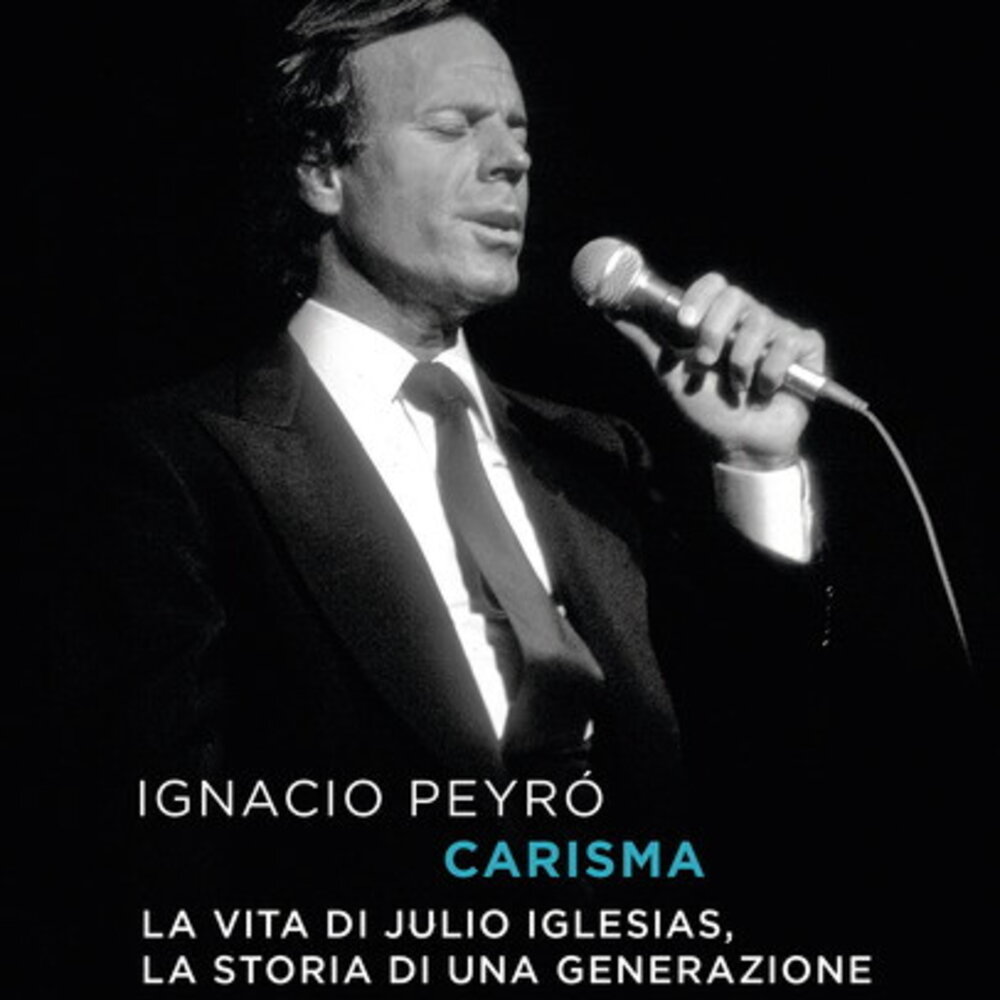

Created by the Spanish government in 1991 to promote and spread Hispanic language and culture around the world, the Cervantes Institute covers 5 continents with 88 centers located in the main cities of 45 countries. Since 2022, the one in Rome has been directed by Ignacio Peyró, a Madrid-based writer and journalist from El Pais who has just arrived in Italian bookstores with ‘Carisma’ (Ponte alle Grazie), a biography of Julio Iglesias which in addition to the life of the famous singer of ‘Se mi lasci non vale’ retraces the recent history of his nation. An editorial operation so original that it pushed AGI to ask its author for information.

Why did you choose Julio Iglesias to talk about the last 60 years of his country?

At the beginning, I actually didn’t know that the project would take this form. I started from the idea of telling the human adventure of an exceptional character, only to then realize that Spain’s recent history could be retraced through his. Iglesias’ story accompanies that of the nation: he was already famous in the last years of Francoism, as an exponent of the popular culture of the time, but then he sang on 15 June 1977 on the election night in which Spanish democracy was reborn, and finally, when the terrorist threat of ETA shook the country, he was a first-hand victim with the kidnapping of his father.

As a man of the right, he had a happy relationship with all socialist politicians, representing the face of Spain which opened up to the world together with figures such as King Juan Carlos, Adolfo Suàrez, Felipe Gonzales and the golf champion Severiano Ballestreros. Forty years ago Julio sang at the White House, establishing himself as the first successful Spanish speaker even among non-Latinos, so much so that he even conquered the very difficult English-speaking public. With his over 300 million records sold worldwide, when they were actually bought, he was a pioneer in the diffusion of a culture and a language that 60 million people now speak in the USA. After him, what was a minority acquired visibility and dignity. His path paved the way for many other artists, from Jennifer Lopez to Bad Bunny.

What does Iglesias think of his book?

This is not an authorized biography, but when I started writing he was informed about it and his manager contacted me, telling me he was happy. In addition to tracing a portrait of him from a cultural point of view, an unusual aspect for the character, the book is having excellent feedback: released in March, in Spain it is now almost at its fifth edition, as well as having been distributed throughout Latin America and translated into Portuguese, French and Italian.

Avowedly right-wing from the beginning, not only was Iglesias able to maintain his success even in post-Franco Spain, but he increased it to the point of becoming a national glory: how was this possible?

I believe two factors contributed. First of all, it must be said that the popular culture of late Francoism had such an influence throughout the country that it survived the arrival of democracy. Furthermore, at the end of the ’70s, Iglesias realized that he had to take a decisive step by moving to Miami, just when music was modernizing in Spain and the so-called ‘movida’ was born. If he had stayed, the new wave would have made him old, but he had already reached a global audience and was representing Spain in the world while also opening a bridge to Latin America.

With his being a star, how much did the character Iglesias contribute to the birth of the so-called gossip journalism?

Very much. The attention paid to him and his first wife Isabel essentially determined the birth of a genre of journalism in Spain, which over the years would enjoy enormous success: the so-called press of the heart. In this sense too he was a pioneer. Its impact on the popular imagination represents a profound imprint left on our culture.

Hand on heart on stage, 3000 declared female conquests: how would Julio be judged today by a public opinion with completely changed ethics?

I think that kind of character wouldn’t be accepted. His fame as a Latin lover was born in the early 1980s after his separation from Isabel, when the staff who followed him decided that a womanizing image could help fascinate the global public. Unlike others, however, Iglesias never fell victim to the so-called ‘cancel culture’, having truly been a sex symbol. Women adored him: more than a predator, Iglesias could almost be called a prey.

In recent years Cervantes’ language has become the Esperanto of world music: does Spanish owe more to Iglesias, or does Iglesias owe Spanish?

Hard to say. I think that Julio was providential for the spread of our language around the world, but that he also arrived on the international scene just when Spanish was starting to become important. I would say we can talk about an equal relationship.

What remains of the myth of Julio Iglesias in the Spain of 2025?

Here, the month of July is called Julio. And every time he arrives we exchange funny messages and memes with Iglesias as the protagonist: ‘here’s Julio’, ‘Julio is hot’, ‘Julio is leaving’. Even today, the affection it arouses remains enormous.