Friedrich Schlegel saw the birth of the new novel with Goethe’s “Wilhelm Meister”: In contrast to other representatives of the genre, here one could read a literature that meant a departure from heroic stories of the past. The hero had become an everyman, about whom the story was told in an open, unfinished form. A post-heroic novel before the word existed.

In “Told World” the literary scholar Steffen Martus embarks on his own years of wandering through our present. He brings with him his guiding thesis, which he developed based on Schlegel’s text on Wilhelm Meister: Open narrative forms require open minds. Caution is advised where longings for heroic stories and closed narratives arise.

“Told World” is not a literary history of the present, but a history of the present through the eyes of contemporary literature. In 1989, Martus began his present. On November 4th, hundreds of thousands gathered on Alexanderplatz to demonstrate for civil liberties. Among the prominent speakers: Christoph Hein, Stefan Heym and Christa Wolf.

When the GDR fell, literature was in the front row; the authors “were seen as mouthpieces of the zeitgeist in this situation, as people who were particularly sensitive to the historical mood and were able to articulate it.” But the two states had difficulties arriving in a shared Germany.

Heroic or post-heroic?

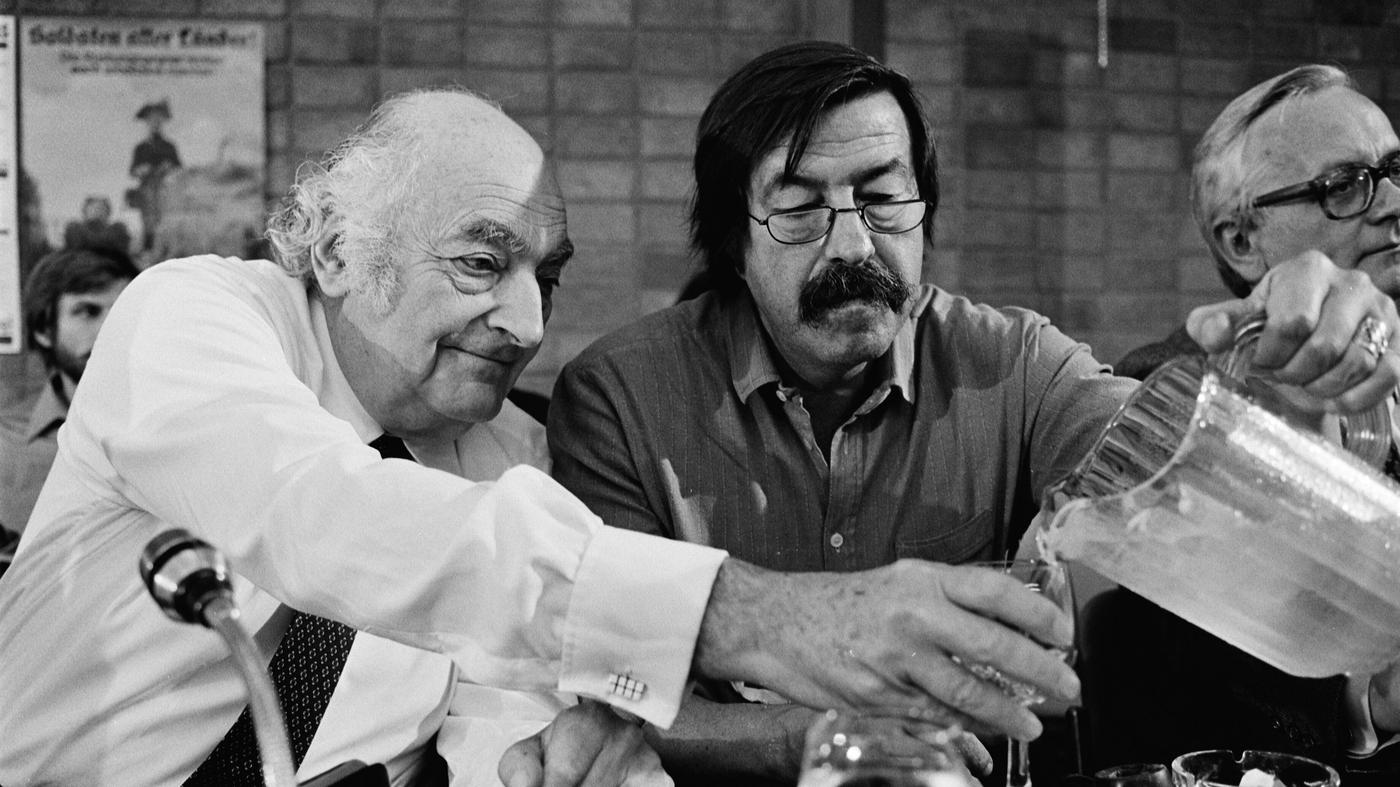

The hole that gaped in the heart of this fused body was supposed to be filled by one great turning point novel, a master story. When Günter Grass tried his version with “A Wide Field” in 1995, he was publicly executed for it by Marcel Reich-Ranicki. With the unification, Martus makes the political dimension of narrative questions clear: Should we tell the turning point as an event of a few heroes or as a post-heroic act of the many?

The new Germany sought its role in the world and literature sought its role in society. Martus traces how the end of the Cold War order triggered a wide variety of defensive reactions. While Peter Handke told his own story of the Yugoslav wars of disintegration, Botho Strauss provided the anti-modern sound for the restrictive years of the new asylum policy under Helmut Kohl.

A new generation had long since formed in their slipstream, authors like Reinhard Jirgl, Thomas Brussig, Rainald Goetz and Thomas Meinecke, who were supposed to lead literature aesthetically into the new millennium. And her successors were already sitting on her shoulders: Christian Kracht, Benjamin von Stuckrad-Barre, Sybille Berg on one side, Judith Hermann, Karen Duve, Juli Zeh on the other.

The neoliberal years of the Golf generation began: while solidarity communities were being worked on and style communities were being founded, new enemies were being created in the fight against terror. Literature incorporated popular forms while marketing found its way into the literary world.

I agree that the external content can be displayed to me. This means that personal data can be transmitted to third-party platforms. You can find more information about this in the data protection settings. You can find these at the bottom of our page in the footer, so you can manage or revoke your settings at any time.

Fast forward to the present day, Martus finds a complicated situation: While German-language literature has opened up to migrant voices and their aesthetics, Martus sees the right-wing vibe shift not leaving its mark. Martus asks: “What had the 2010s done to the literary field?”

Fighting with the mainstream

If literature is “society on a small scale,” then from the mid-1900s onwards it also experienced a shift to the right. Authors like Monika Maron and Uwe Tellkamp have been involved in a battle with the mainstream for years and dream of a closed world. Martus Tellkamp counters: “But what if he took politically seriously the creativity processes that apparently determine the work on his novels? The flexibility and shapeability of borders? The ability of novel elements to migrate and integrate? The open future of his writing projects?”

You are finally surprised to find yourself at the end of the path. You’re a little tired and also frustrated because the author takes detours and detours, but what you’re left with is the feeling that you’ve not only learned something about this contemporary literature, but something about the present. In times in which the humanities are coming under right-wing and austerity pressure, Steffen Martus develops a political view of literary forms that is trained on the text.

It is an appeal to understand storytelling as a social practice. Or to put it with Schlegel: “It’s as if everything that went before was just a witty, interesting game, and now it’s getting serious.”