At 2 pm on 3 October 1866, with all the trappings of international law, the peace between the Habsburg Empire and the Kingdom of Italy was signed in Vienna, thus closing the third war of independence which brought the Veneto into the Italian borders. It was the first war of the unitary state which, however, had not yet completed the Risorgimento journey. What seemed like a success on the European scene was actually the result of a double military defeat on land in Custoza and at sea in Lissa, and of a diplomatic defeat that would mark the prestige of the new nation for a long time.

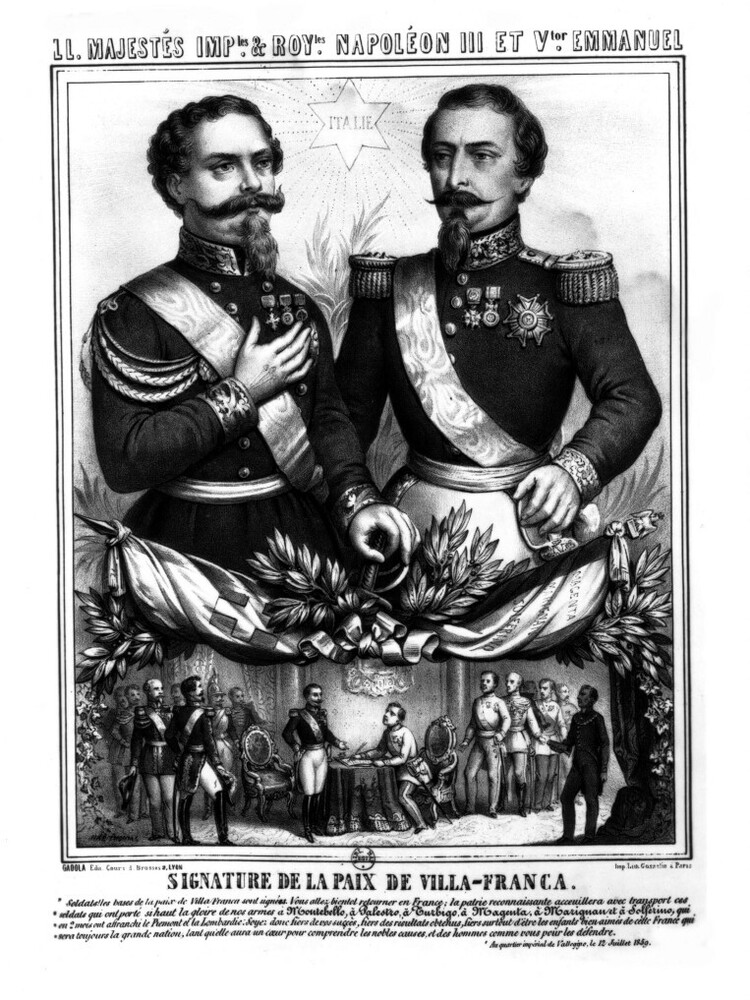

Franz Joseph ceded the territories to Napoleon III to turn them over to Vittorio Emanuele II

When the plenipotentiaries General Federico Luigi Menabrea and Count Emmanuel Felix de Wimpffen for the French Empire signed the treaty in 24 articles, one additional and three protocols, Italy officially accepted from Napoleon III the territories that had been ceded to him by Franz Joseph so that turned them over to Vittorio Emanuele II, as pre-established in the agreement between Vienna and Paris. The Habsburg chancellery had taken great care to ensure that a referendum would be held in the territories in which the population could opt for imperial citizenship, and that Florence would take on the public debt of the Venices, which was anything but light. The King of Italy will ratify the treaty on October 6: it was the result that counted, even if the way in which he had expanded his kingdom was not edifying, even for him who was and felt above all a soldier. As for the Italian soldiers who fought under the flags with the black eagle and had fought for Franz Joseph, they were free to opt for Italy, maintaining ranks and honors in the Savoy army, or remain faithful to their oath to the Habsburgs.

The rivalries and ambitions of the military cause diplomatic humiliation

The victory in defeat was the result of the resounding success of its ally Prussia over the Austrians at Sadowa, on 3 July, which had decided the fate of the war in one fell swoop. The armistice with Berlin was signed on 26 July in Nikolsburg and will become the Peace of Prague on 23 August: Otto von Bismarck with a fine political plan managed to impose himself on William I Hohenzollern who instead toyed with the idea of entering Vienna triumphantly at the head of his troops. The chancellor had guaranteed the integrity of Austria with the exception of the Venices which were included in the treaty of alliance with the Kingdom of Italy, in article 4. The Italian government had not been consulted or informed at all of the Prussian steps towards the end of the war, and he could not bring any military pledge to the peace table because his conduct on the battlefield had been unsuccessful. Florence had to negotiate with Vienna, but could not ask for anything more than what the Prussians had contemplated in the alliance pact. Furthermore, the French newspaper Le Moniteur had made it known to all of Europe that the Veneto would be ceded to Napoleon III who in turn would turn it over to Italy, since Bismarck could not and did not want to ask Austria for the direct cession and not even that the new border followed the natural border of Trento and Bolzano as the Italians wanted. Diplomatic pacts were not these and the chancellor did not intend to bend from this line, neither by continuing the war nor by diplomatically supporting the ally.

Garibaldi’s success thwarted by ‘I obey’ the King’s order

Giuseppe Garibaldi who was marching north with his undefeated red shirts was stopped by an order from the King to which he responded with the famous “I obey” telegram, and so was the Chief of Staff Alfonso La Marmora, architect of the Custoza disaster with the unrealistic general Enrico Cialdini who was now agitated because he even wanted to conquer Trentino after having provided very little evidence as a strategist. In fact, there was no room for a restorative victory. Conducting the war independently was not feasible, because Austria was only waiting to be able to turn its entire army to the south without having to divide its forces under the Prussian threat to the north, and thus settle the score with Italy twice already joke. If all in all Custoza had been a success on points, in Lissa the victory had been absolute and sensational, considering the forces on the field and the gap between the fleet of Wilhelm von Tegetthof and that of Carlo Pellion of Persano which boasted modern battleships but was torn apart by the rivalries between admirals and the lack of caliber of the commanders. The core of the Imperial Kriegsmarine was instead made up of Venetian, Dalmatian and Istrian experts who rejoiced in the waters of the Adriatic on 20 July, praising Saint Mark and the long and prestigious maritime tradition of the Serenissima. Two battleships had sunk and Italy had lost 640 men, while the Austrians had just 38 dead and 138 wounded.

The demands of Vienna and the clauses on plebiscites

For the signing of the armistice, Vienna had demanded the evacuation of all Italian troops, regular and irregular, from Tyrol, referring precisely to the Garibaldians who had won the only victory of that war at Bezzecca, on 21 July, continuing into enemy territory. Italy had not even been allowed to negotiate with the strong point of the uti possidetis and the Prime Minister Bettino Ricasoli had therefore ordered the withdrawal, as ordered by Archduke Albert, by 4 in the morning on 11 August. At the Italian-Austrian negotiations that would have brought about the 1815 borders between Lombardy-Veneto and the empire, Napoleon III had sent his aide-de-camp, General Edmond Le Boeuf, as commissioner, and every Italian attempt to avoid international humiliation was useless. The ploy of the royal decree of October 3rd to call plebiscites for the 21st and 22nd will not succeed in removing the French veto on the entry of Italian troops into Venice and Verona before the outcome of the vote. Le Boeuf, with common sense, will still cede the Veneto to the Kingdom of Italy on 19 October, not in a prestigious location but in the anonymity of a room in the Hotel Europa in Venice. Two days later the passage under the crown of Savoy will be officially sanctioned by 641,758 yes (99.99%), 69 no and 273 abstentions. It should be underlined that in the peace treaty Franz Joseph limited himself to magnanimously giving his “assent to the reunification of the Lombardy-Veneto kingdom with the kingdom of Italy”, and the triumphal entry into Venice of Vittorio Emanuele II and the wave of rhetoric they will not be able to dilute the reality of the facts nor to overcome the embarrassing historical, political, military and diplomatic anomaly represented by the Third War of Independence.