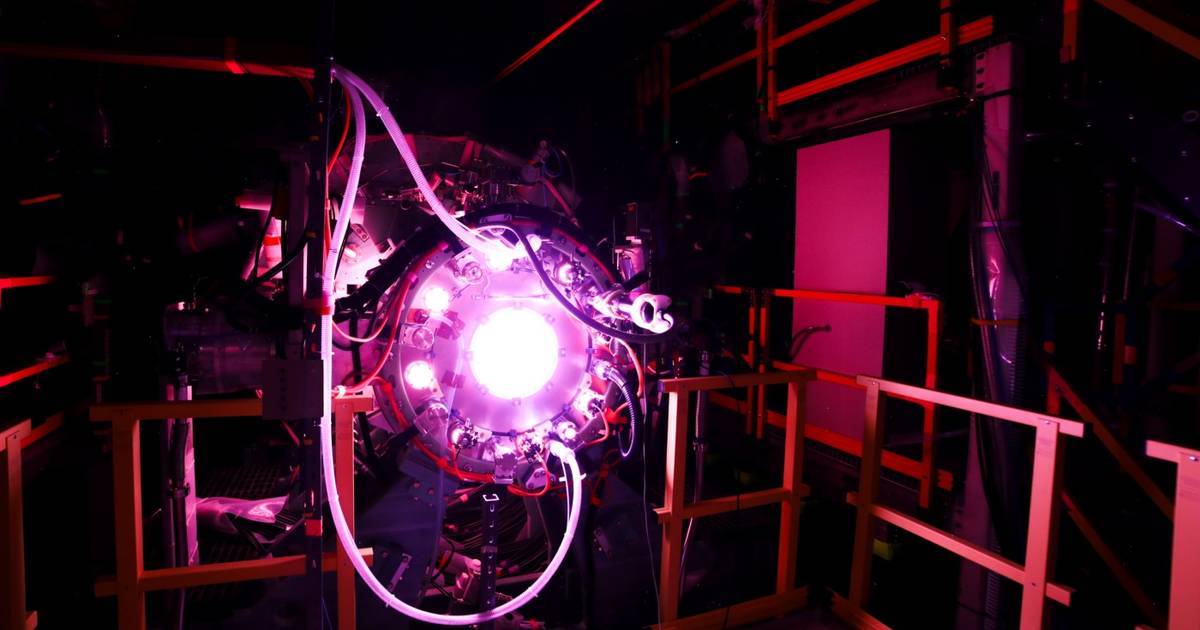

American company Helion Energy announced two key breakthroughs in the race to commercialize fusion energy. Their seventh prototype, named Polaris achieved a plasma temperature of an incredible 150 million degrees Celsius and became the first privately developed fusion machine to successfully demonstrate fusion using a deuterium-tritium (DT) fuel mixture. These steps represent huge progress towards Helion’s ambitious goal of delivering fusion energy to the electric grid by 2028.

Record temperature and key fuel

Reaching a temperature of 150 million degrees Celsius is not only an impressive number, butć and a key technical prerequisite. That’s ten times hotter than the core of the Sun, and in industry the 100 million degree mark is considered the threshold for a commercially viable fusion power plant. With this result, Helion broke its own record of 100 million degrees, which was set by their previous sixth-generation prototype, Thirty.

Equally important is the fact that Polaris is the first private system to conduct tests with deuterium-tritium fuel. Although Helion’s ultimate goal is to use a purer mixture of deuterium and helium-3 (D-He3), the demonstration of operation with DT fuel confirms that their system is capable of working with different fuels and validates their engineering approach. Helion is also the first private company to receive regulatory approval for the possession and use of radioactive tritium for the purposes of fusion research.

- We believe that the surest path to fusion commercialization is to build, implement, and iterate as quickly as possible. We have built and operated seven prototypes, each time setting and exceeding more ambitious technical and engineering goals – said David Kirtley, co-founder; and CEO of Helion.

– The historic results of our test campaign with deuterium-tritium on Polaris confirm our approach to the development of high-power fusion and the excellence of our engineering – he added.

A unique path to čsame energy

Helion’s approach to fusion is significantly different from most other projects, such as those using large donut-shaped tokamak reactors. The company uses a pulsed magneto-inertial system, where two rings of plasma are fired at each other at high speed inside a chamber. When they collide, strong magnetic fields compress them, raising the temperature and pressure to the point where fusion occurs. The whole process takes less than one millisecond.

The biggest innovation lies in the way Helion plans to collect energy. Instead of using the heat of the fusion reaction to drive steam turbines, as conventional nuclear or thermal power plants do, their system captures the energy directly. As the plasma expands during fusion, it pushes the magnetic field that surrounds it, which induces an electric current in the reactor coils. This converts the energy directly into usable electrical energy, which makes the system potentially significantly more efficient and smaller.

The race to 2028 and the contract with Microsoft

These technical achievements are not only of an academic nature; they are the foundation of Helion’s aggressive business plan. The company, čiji is the chairman of the board and one of the main investors Sam Altmanbutć has signed the world’s first agreement on the purchase of fusion energy with the technological giant Microsoft. The goal is to deliver at least 50 megawatts of electricity to the grid by 2028.

Based on results from Polaris, Helion is moreć began construction of its first commercial power plant, called Orion, in Malaga, Washington, not far from Microsoft’s growing data center campus. Parallel development and rapid iteration are a key part of their philosophy, which, according to Kirtley, has allowed them to progress faster than the competition.

The progress was also recognized by the scientific community. Jean Paul Allain of the US Department of Energy’s Office of Science said: “Seeing data from the Polaris test campaign, including record temperatures and fuel mix gains in their system, indicates strong progress.” A similar comment was made by Ryan McBride, a fusion expert and professor at the University of Michigan, who said it was “exciting to see evidence of DT fusion and temperatures exceeding 150 million degrees Celsius.”

https://mostbet-tr-online.com/faq

https://mostbet-tr-online.com/legal

https://mostbet-tr-online.com/login

https://mostbet-tr-online.com/mirror

https://mostbet-tr-online.com/mobile

https://mostbet-tr-online.com/payments

https://mostbet-tr-online.com/problems

https://mostbet-tr-online.com/promocodes

https://mostbet-tr-online.com/reviews

https://mostbet-tr-online.com/slots

https://mostbet-tr-online.com/support

https://mostbet-tr-online.com/withdrawal

https://mostbet-pl-online.com

https://mostbet-pl-online.com/apk

https://mostbet-pl-online.com/app

https://mostbet-pl-online.com/bonus

https://mostbet-pl-online.com/casino

https://mostbet-pl-online.com/deposit

https://mostbet-pl-online.com/download

https://mostbet-pl-online.com/faq

https://mostbet-pl-online.com/legal

https://mostbet-pl-online.com/login

https://mostbet-pl-online.com/mirror

https://mostbet-pl-online.com/mobile

https://mostbet-pl-online.com/payments