Rishi Sonak’s act on June 6 is hard to understand. The young and graceful Prime Minister of Great Britain, struggling almost hopelessly for his political life, decided to cut short his presence on the northern coast of France, and to be absent from the high-profile international commemoration of the military operation that made possible the liberation of Europe from Hitler, exactly 80 years earlier.

Sunak, Britain’s first ever non-white, non-Christian Prime Minister, decided that taping a TV interview was more important than taking a selfie with all the leaders of the Western world. It was strange even from the electoral point of view: a high profile is exactly one of the advantages that prime ministers have during an election campaign. They continue to enjoy attention that stems from their position, not necessarily from their personality. This is what is called in America “the seniority advantage”, which is often the difference between defeat and victory.

Sunak was quick to apologize, but a huge scandal broke out. Its part is of course self-righteous pretense – parties always pretend that their opponents’ testimony is the greatest and most terrible in the annals of history. But Sunak’s anti-gestation was an expression of frivolity, perhaps even of lightness, and as such it was well deserving of rebuke.

But there was one politician who added an explanation from another category, which derives from it an ethnic, or even racist, allusion. Nigel Farage, leader of a small right-wing, immigration-hating, Trump-loving party, declared that Sonak’s departure from the beaches of Normandy proved he was “not a patriot”. It was hard to mistake Faraj’s intention: Sonak, the son of Indian immigrants from East Africa, a member of the Hindu religion, does not love his country.

He did not acquire the nostalgia in his home

In itself this is a losing and dangerous declaration, which the title “white supremacy” certainly deserves. But after the unequivocal moral condemnation, perhaps it is permissible to ask whether Sunak’s ethnicity, or that of any person, plays a role in shaping his opinions, understandings and insights.

Sonak is British to all intents and purposes, and there is no reason to doubt his patriotism. But isn’t it possible that his love for his homeland is based on a different life experience? Furthermore, in a society of immigrants (Britain has indeed become such a society in the last half century) is the love of country repeated and defined more than once in a way that does not agree with the original definition?

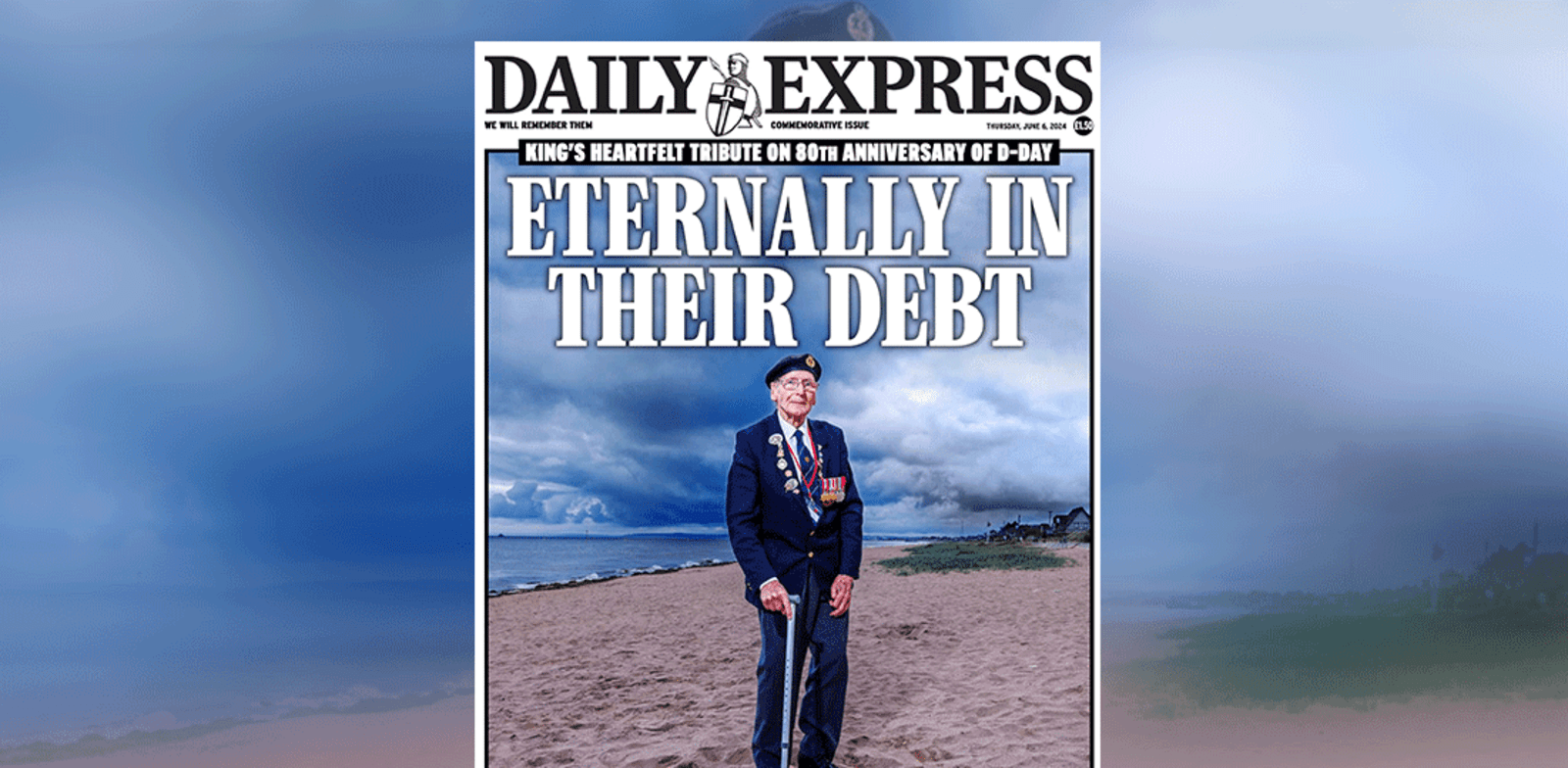

The 80th anniversary of the beginning of the liberation of Europe was the defining event for previous British generations. When General Eisenhower spoke on the radio in the ears of the 150,000 soldiers who moved to the beaches of Normandy (almost half of them were killed), he described the invasion as a “crusade”. This is not necessarily a religious characterization, despite the cross; But at least in this context it had a religious aspect. This is how it was perceived: as an effort by “Christian civilization” to expel Satan.

When Roosevelt and Churchill met for the first time, in the summer of 1941, aboard a British warship in the Atlantic Ocean, they sang, during Sunday Mass, the Anglican prayer hymn, “March on, Christian soldiers.” The hearts of elderly history buffs continue to beat faster every time they watch that class (see on YouTube).

Is it possible to demand, or expect, a non-European and non-Christian person to react with the same excitement? Sunak is a westerner, but he may not have the cultural nostalgia that a westerner acquires in his parent’s house.

In addition, there are many Indians in Britain, and of course in other places, who know what Churchill did in India in the very days when he saved Western civilization in Europe: in 1943 he allowed a threatening famine to spread in Bengal, on the east coast of India. We have evidence that he knew full well what was going on, shrugged his shoulders, and didn’t lift a finger. Three million people may have perished. Isn’t it reasonable to assume that British people of Indian origin would have mixed feelings about him and about saving Western civilization?

This matter is of course much wider and more complex than that of Indians in Britain. It concerns the long-term consequences of the diminishing identification of immigrants with the historical heritage of their countries of residence. Are African or Muslim immigrants in America filled with excitement when they hear about the “founding fathers” and the “framers of the constitution”? Boys are excited.

“Millionaires’ Pool”

Last week, a painful article on Channel 12 about the destruction of Hanita conjured Menachem Begin’s failed incitement in 1981 against the “pool of millionaires” of the kibbutz. He didn’t bother to mention that the founders of Hanita were bold pioneers, and if it hadn’t been for their daring, it is possible that the northern border of Israel would have passed somewhere near Tivon. But does Hanita’s 1938 heroism speak to the hearts of most Israelis?

I repeat and find it difficult to understand how the labor movement in Israel managed to almost completely miss the centenary year of the second aliyah (2003), and again missed the 120th year. Of course, the labor movement is nothing but a pale shadow of what it was, but at least part of the explanation for the omission is that most Israelis would shrug their shoulders. What do they care what socialist pioneers did in Odessa in 1903, which ship they got on, and where they got off.

Historical memory is necessarily limited. There is no point in complaining about that. But a society begins to pay a price when the important events of its life are interpreted in opposite ways and do not arouse the same degree of excitement or interest. I think a considerable price has been exacted from a society separated from its founding moments of heroism, whether because of the shortness of memory, whether because of cultural antagonism, or out of boredom.