In pursuing its mission to celebrate the seventeenth century and the Baroque in all its artistic forms, the Borghese Gallery puts to the test four centuries later the inquisitorial ideas of its founder, the cardinal collector Scipione Borghese. From 19 November to 9 February, an exhibition is dedicated to the poet Giovan Battista Marino which challenges those who opposed him in every way in the papal Rome of the Counter-Reformation, in an ideal belated reconciliation between the two great figures.

“Poetry and painting in the seventeenth century. Giovan Battista Marino and the marvelous passion” tells, in the rooms which reopen for the occasion after a restoration still underway in other parts of the museum, the connections between poetry and painting, sacred and profane, literature, art and power at the beginning of the seventeenth century. It is the director Francesca Cappelletti herself who highlights the paradox of “setting an event here exhibition dedicated to Marino, who never managed to become the patronage of Cardinal Borghese”. The link between poetry, painting and sculpture allowed by the setting in the realm of the Baroque is the practical expression of that “gallery dreamed and imagined” by the poet, in the same years in which the cardinal concretely created it in the nascent Galleria Borghese. But it was the same cardinal-collector who was one of the main accusers in the inquisitorial trial that would lead Marino to abjure his work and to a new exile from Rome, following the publication in France of the poem Adone.

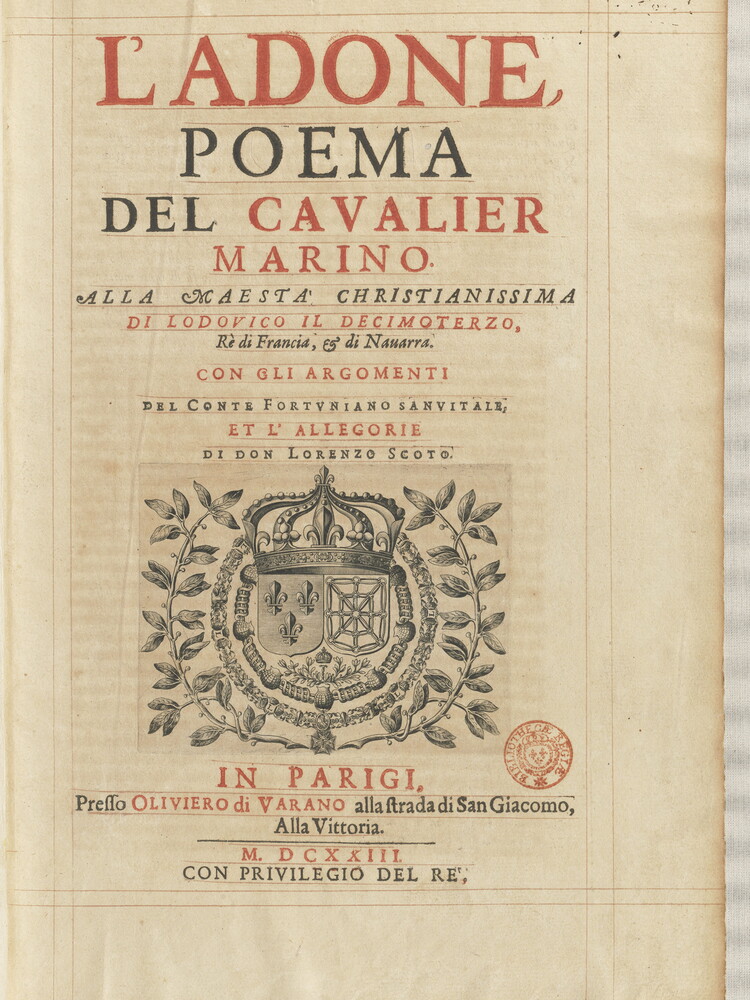

A vintage copy is displayed in the first room of the exhibition; at the top, on the first page of the richly bound volume, the handwritten “Prohibited 1st class” appears. In other words, explained one of the curators, the literary historian Emilio Russo, “you shouldn’t even look or touch it”. And to say that at the time Adonis had been authoritatively defined as a “poem of peace” in which sensuality and beauty attempted to counteract a warlike era and to “ward off the pain of war”.

The dangerous game of Marino, and of many of “his” painters, between the sacred and the provan was seen in times of the Counter-Reformation and the Inquisition as an unacceptable contamination, which the Roman exhibition valorises even more so. The exhibition uses Marino’s texts to draw “a path through the great Renaissance and Baroque art, from Titian to Tintoretto, from Correggio to Carracci, from Rubens to Poussin, celebrating the greatest Italian poet of the seventeenth century and his wonderful passion for painting”, in addition to his relationships with artists, including Caravaggio who almost certainly met and became a friend, to the point that a letter from his nephew even mentions a Caravaggio-style portrait of the poet, now lost, which is described as being displayed on the same wall as another painting dedicated by the great contemporary painter of light precisely to him, his “enemy” Scipione Borghese.

Marino’s ambition as a collector was dashed by a mysterious loss of works on a sea voyage from Paris to Rome and his project was interrupted by his death at the age of 56 in his native Naples, almost exactly 4 centuries ago, just as he was about to build the large house museum he had always wanted.