Guadalajara, Jal., The public fang y El ahuizote jacobino They were precursors of the Mexican Revolution by becoming magazines that were born and developed to criticize the dictatorial and reelectionist spirit of Porfirio Díaz and, despite the repression and imprisonment suffered by their collaborators and directors, including the Flores Magón brothers, they also laid the foundations for a transformative cultural movement, said Rafael Barajas. The Snooper.

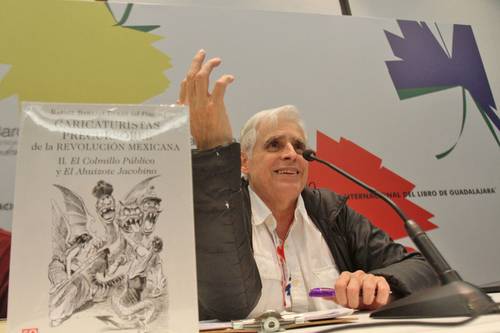

The cartoonist presented the second volume of the saga Caricaturists who were precursors of the Mexican Revolution in the context of the Guadalajara International Book Fair (FIL).

Rafael Barajas (Mexico City, 1956) recalled that both publications were worthy successors of The son of the ahuizote, magazine that was characterized by seeking to raise awareness among the people through caricatures that, in addition to exposing the reality of the country, had the luxury of mocking and ridiculing the figures of power.

Edited by the Economic Culture Fund, the National Institute of Anthropology and History and the federal Ministry of Culture, the 510-page copy documents the journalistic and political caricature contribution that served to form the nuclei that managed to be decisive during the Mexican Revolution and then during the first years of the governments that emerged from it.

“The ahuizote It always stood out for being a wrestling magazine, all its members were part of the Tuxtepec group, which was angry with Porfirio Díaz. They then launched The son of the ahuizote who criticized Díaz’s re-election, but people did not fight him because at that time Díaz had extraordinary prestige.”

The caricaturists portrayed him as a king seeking permanence on the throne, no longer with a scepter, but with the sword. For years no one took the publication into account, and in 1893 a first anti-reelection movement emerged; From then on, the Porfiriato took the magazine more seriously, “which it must be said was very repressed.”

Faced with criticism, Díaz established the “gag law,” despite which the publication continued to appear, which forced the President to take other measures, such as imprisoning the cartoonists and the director.

The brothers Jesús and Ricardo Flores Magón entered the scene, very young in that anti-reelectionist movement, but they were beaten so badly that they withdrew from activism, in addition to the fact that the director of the magazine, Daniel Cabrera, was taken to trial, during which he had a cerebral infarction and became hemiplegic, so he decided to hand over the direction to his nephew Luis Cabrera, 19 years old, who in the end would be the ideologist of Carrancism.

The Flores Magóns returned to public life with the magazine Regeneration to defend Cabrera, who was imprisoned, and the magazine little by little became radicalized: from consistent liberals they became socialists.

The historical account of Barajas, who obtained the John Simon Guggenheim scholarship in 2002 for his research work on political caricature, detailed that for the first time the Porfiriato was undermined by the real impact of the criticism that managed to “throw down” Bernardo Reyes, Porfirio Díaz’s right-hand man and Secretary of War and Navy, from his position.

Ricardo Flores Magón’s national project was published in The public fang, to put it up for public discussion. Then it was taken to Regeneration and soon it became a program and the basis of the 1917 Constitution.

“Caricatures were the basis of the Mexican Revolution; they were crucial and then ignored for a long time. Art can transform society and here is an example; it does so by linking to political movements, articulating and promoting. It is an art of commitment,” says Barajas.