Delving into the life and work of the master of modern realism Edward Hopper (1882-1967) can be overwhelming, especially when you think that everything has probably already been said. The point is to see what others have not noticed. At least that was the case for Alejandro Pérez Cervantes, author of Edward Hopper in northern Mexico, who highlights the influence that the greatest exponents of muralism in our country had on him, distances himself from the usual Hopperian clichés proposed by his traditional reading.

The book, published by the Autonomous University of Nuevo León (UANL), has aroused such interest since its publication that some museums in Monterrey are considering allowing the work that Hopper produced during his stay in Mexico to visit the country for the first time next year, in a traveling exhibition in Nuevo León, Mexico City and a museum in the United States, something that would be a real event in the artistic world

the author revealed for The Day.

The artist, who also holds a PhD in critical theory from the Institute of Critical Studies and a master’s degree in editorial design from the University of Monterrey, sought in his research to reveal not only the formal, but also the stylistic and symbolic routes with which the American artist constructed his Mexican work.

When I started reading the bibliography, I realized that he is a very well-studied author, but always from the same perspective. I also wanted to delve deeper into his life and work, but with a different interpretation, from our country, trying to understand the classic theory of art.

Pérez Cervantes stressed the importance of the Hopper couple’s first trip to the country. According to the written testimony of Josephine Nivison, her husband was looking for new landscape motifs.

Thus, his first trip began on June 29, 1943, arriving in the Mexican capital on July 3 and staying at the Ritz Hotel on Madero Street.

When he made his first trip in 1943, he became familiar with Mexican mural art and saw the work of Rivera, Siquerios and Orozco. His wife mentions that Hopper was moved and influenced by them. However, in the capital they did not find anything that convinced them, so the curator of the Art Institute of Chicago, Katherine Kuh, recommended that they visit Saltillo; there they were dazzled by the deep blue of its skies, in intense contrast with the grey, green, reddish and ochre colours of its buildings.

.

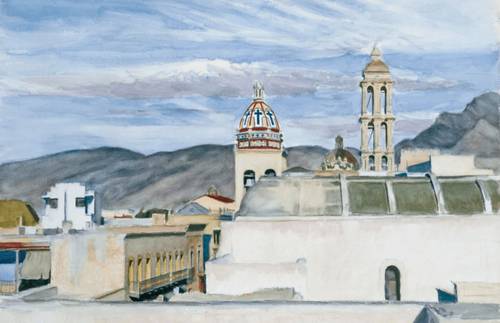

The watercolor Saltillo Rooftops is the result of this visit, as well as Sierra Madre in Saltillo y Saltillo Mansion, one of his most beautiful works painted on that visit.

When he returned to Mexico on his second trip in 1946, after both had studied Spanish, Hopper began to paint the landscape of northeastern Mexico, leaving aside the people, in an invitation to contemplate the natural views, with the mountains of the Sierra Madre de Saltillo and Monterrey bathed in the northern light, which is very transparent and warm.

Unlike Nighthawks, One of the painter’s most iconic pieces, in which he showed the United States of the Great Depression, works such as Church of St. Stephen, The Palace y Construction in Mexico, that the artist of silence

Conceived during his second visit to Mexico in 1946, they become a more metaphysical meditation on the condition of solitude, without any human trace, only spaces, plays of light and architectural forms.

In 1951, Oaxaca was also the destination of the Hoppers, where he made his last pieces of the Mexican period: Mountains at Guanajuato y Cliffs near Mitla. However, in all his visits the role of his wife, Josephine Nivison, better known as Jo Hopper, was invaluable to the painter.

Jo Hopper’s diary and letters, her reconstruction of her daily life in Mexico, were invaluable. Without her testimony we would know nothing of what happened 80 years ago; that is Jo’s contribution to Hopper’s life. Moreover, in a time of deep-rooted machismo, she fought for her place in those years. We owe all of Edward Hopper’s knowledge and legacy to her.

Pérez Cervantes said.

Her visionary role was not limited to everyday life and practical ends. She thought of posterity after donating almost 800 works and more than 3,000 drawings, engravings and notes to the most important museums in the United States after her husband’s death, knowing that she was preserving his art.

As he himself writes, One of the undoubted and unforeseen discoveries of this research was to discover the fundamental role played by Jo in the construction of the artist and in the consolidation of his myth. It cannot be ignored that her work, who was also an artist, even influenced Edward’s work aesthetically in a direct way. In addition, she was often in charge of naming her husband’s paintings. She accompanied him, trained him, survived him.

.