How the first men came to America remains a mystery. The most widely accepted theory is that an ancestral Siberian people crossed the Bering Strait during the last Würm Ice Age (sometime between around 110,000 years ago and around 9700 BC), colonizing the entire continent from north to south. However, recent finds pointed towards a possible earlier conquest. Now, the study of the largest body of genomic data from Brazil, including the DNA of Luzio, the oldest skeleton found in Sao Paulo, is shedding new light on the origins of these early Americans: Luzio, who lived about 10,000 years ago, was a descendant of of the ancestral population that settled in America at least 16,000 years ago and gave rise to all current indigenous peoples, including Tupi, Guarani or Cherokee. The conclusions have just been published in the journal ‘Nature Ecology & Evolution’.

The authors also wanted to explain the reason behind the sudden disappearance of the oldest coastal communities, which built the so-called ‘sambaquis’. Also known as shell dumps and present on other coasts throughout the world, sambaquis are huge mounds of shells and spines that were used as a kind of ‘dumps’ in which they mainly deposited the hard parts of molluscs, with which they mainly These peoples fed themselves, but also bones and even ceramics.

“After the Andean civilizations, the sambaqui builders of the Atlantic coast were the most densely populated human phenomenon in pre-colonial South America,” explains André Menezes Strauss, an archaeologist at the Museum of Archeology and Ethnology of the University of São Paulo ( MAE-USP) and principal investigator of the study. “They were the ‘kings of the coast’ for thousands and thousands of years. But suddenly they disappeared about 2,000 years ago.”

Reconstructing history through genomes

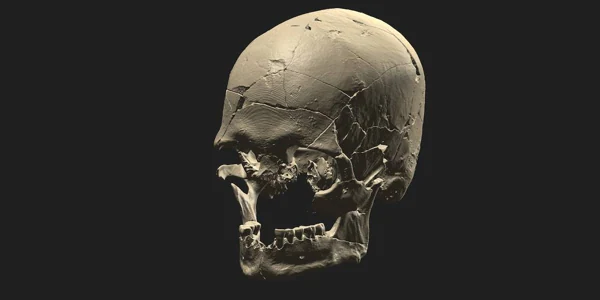

The authors analyzed the genomes of 34 samples from four different areas of the Brazilian coast. The fossils were at least 10,000 years old and came from sambaquis and other sites (specifically, Cabeçuda, Capelinha, Cubatão, Limão, Jabuticabeira II, Palmeiras Xingu, Pedra do Alexandre and Vau Una). Among the human remains, those of the aforementioned Luzio, the oldest skeleton in São Paulo and which was found in the shell midden of the Capelinha river, in the Ribeira de Iguape valley, by a group led by Levy Figuti, a professor at MAE-USP.

The morphology of its skull is similar to that of Luzia, the oldest human fossil found to date in Brazil, dating back about 11,400 years. The researchers thought it might have belonged to a population biologically different from today’s Native Americans, who settled in what is now Brazil around 14,000 years ago. But they were wrong. “The genetic analysis showed that Luzio was Amerindian, like Tupi, Quechua or Cherokee,” Strauss says. That’s not to say they’re all the same, but from a global perspective, they all derive from a single migratory wave that reached the Americas no more than 16,000 years ago. If there was another population here 30,000 years ago, it left no descendants among these groups.”

Same in base, but with differences

Luzio’s DNA also revealed that there were two distinct migrations: one inland and one along the coast. Analysis of the genetic material revealed heterogeneous communities with cultural similarities but significant biological differences, especially between the southeastern and southern coastal communities. “Cranial morphology studies conducted in the 2000s had already pointed to a subtle difference between these communities, and our genetic analysis confirmed this,” Strauss notes. “We found that one of the reasons was that these coastal populations were not isolated but ‘exchanging genes’ with inland communities. Over thousands of years, this process must have contributed to regional differences among the sambaquis.”

Because the sambaquis on the coast were not the same as those in the interior, near the rivers, although they were similar, proving that there were relationships and contact between them. Now the ancient DNA also reveals that it was more than a matter of culture.

Why did the sambaqui builders disappear?

As for the mysterious disappearance of this coastal civilization, analysis of the DNA samples clearly revealed that, in contrast to the European Neolithic replacement, in which entire populations nearly ‘evaporated’, what happened in this part of the world was a change in practices, with a decrease in the construction of sambaquis and the introduction of ceramics. For example, the genetic material found in Galheta IV (Santa Catarina state), the most emblematic site of the time, does not have remains of shells but of ceramics and is similar to classic sambaquis in this respect. That is to say: they changed the shell sambaquis for ceramic ones.

“This information is consistent with a 2014 study that analyzed pottery shards from sambaquis and found that the pots in question were not used to cook domesticated vegetables but rather fish. They appropriated technology from the interior to process foods that were already traditional there,” says Strauss. Other studies have pointed out that it was climate change, specifically the decrease in sea level in the Atlantic Ocean, with the decline of these ancient civilizations.