Since their discovery in July, fourteen paintings have been groomed under the noses of the State services by an amateur and volunteer painter.

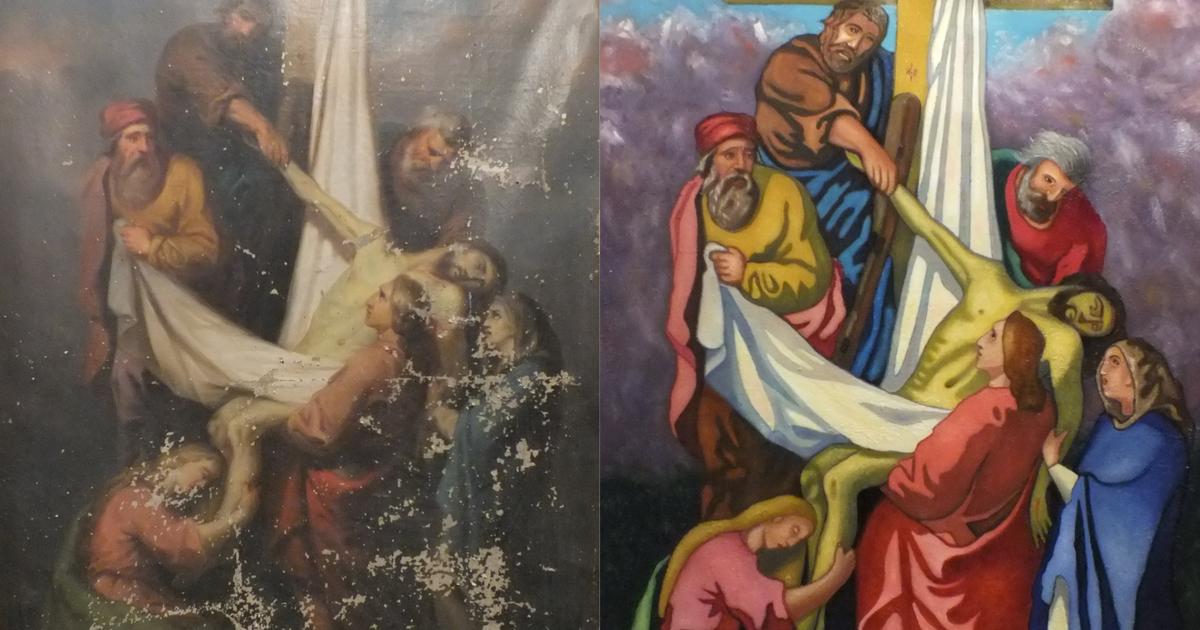

In the tower of the Saint-Brice church in Chatonrupt-Sommermont, Haute-Marne, the fourteen stations of Christ’s ascent to Calvary were destroyed. In the hands and amateur brushes of a town retiree, they have been given new life and color. Painting after painting, the canvases’ peeling surfaces and faded tones give way to brighter colors, firmer forms, and the impression of having “fixed” a sequence of oil paintings that had been left to degrade for far too long. Except that the volunteer restorer had no idea that his brushstrokes had wounded works of art that, according to preliminary estimations, date from the mid-nineteenth century.e century.

The mayor of Chatonrupt-Sommermont, Jol Agnus, told the Figaro, “It started with a pleasant sentiment, but that’s how it is, the damage is done.” Sorry for the tone. In this small village located between Troyes and Nancy, almost no one had remembered the presence of these anonymous paintings depicting Christ in agony. This set, discovered in July 2021 while working on the church’s carillon, depicts the fourteen stations of the Way of the Cross, one of the primary motifs of Christ’s passion. Around 1973, the group of paintings was consigned to the darkness of an unknown area of the bell tower, unprotected by a tarpaulin or any other means. Between an unsteady stairway and a bay open to the four winds, the canvases stayed hunkered in their blind place, black and stinky. Squadrons of pigeons and owls appeared to be courting them there.

The paintings sat in an unhygienic corner of the Saint-Brice church in Chatonrupt-Sommermont, Haute-Marne, for decades. Patrick Quercy is a writer who lives in France.

When it was uncovered, Chatonrupt-pictorial Sommermont’s “prize” had deteriorated into a jumble of rotting canvases. The mayor recalls the incident. Joel Agnus adds, “At first, we thought of a pile of decaying wood.” The frames were worm-eaten, the colors were faded, the canvases were ripped, and the paint dropped down with the twenty centimeters of pigeon droppings as soon as one attempted to clean them, however insignificantly. According to the testimony of several village elders, these same paintings, which were shown in the nave of the church in the 1960s, were already in a state of disrepair. The whole thing has been chiseled out by prolonged solitude. “Our initial instinct was to toss everything in the trash,” says the mayor, “and that’s exactly what we would have done if our volunteer hadn’t volunteered to restore what may have been.”

A restaurant that is well-liked by the locals.

Patrick Quercy, the volunteer in question, was making his first attempt at art restoration. After sanding the frames, cleaning the surface, and varnishing the canvases, this retired Air Force meteorologist who openly characterizes himself as a “free thinker” began to work on restoring them to their former glory. He had purchased “excellent” equipment for the occasion in a Joinville DIY store; an investment for which he charged the town council 40 euros per restoration – enough to cover the costs incurred.

They were third-rate canvases, mass-produced in a rush in factories by small local painters who sold them by catalog.

Patrick Quercy is a writer who lives in France.

The prospect of rehabilitating these works is gaining traction. “The volunteer painter to the Figaro observed, “I saw that they were not signed and that it was merely a derisory Stations of the Cross.” I made a video of myself. After 1815, this style of painting became popular in France. They were third-rate canvases, mass-produced in a rush in factories by small local painters who sold them by catalog. They were also scraped and smeared in pigeon feces.” In summary, according to the passionate retiree, the debris of performances on a sacred subject, but of a culinary kind, and bungled up by jobbers.

The artworks discovered in the small village are unclassified and in a deplorable state. “According to Patrick Quercy, it’s as if we found them at the recycle facility. Because the artworks were on the verge of being destroyed, they could have easily been torched. By the way, another mayor would have done it without a doubt.” Last summer, the town government made the decision to restore the tables and “make them presentable” before reinstalling them in the church. “It was my objective. I went along with it. “At no point did we think this would be a problem,” the amateur restorer asserts, omitting to cite the heritage code or the paintings’ inalienability.

Christ’s death on the cross. In Haute-Marne, the XIIe Station of the Cross was recently repaired. Patrick Quercy is a writer who lives in France.

In the slumber of the summer of 2021, the big labor begins. The first canvas is taken up again with very caution, and new layers of paint are applied gradually, following the outline of the original piece. To be sure, the style is unique, and the colors are unexpected. According to the volunteer, due to the losses and faded colors, it had become «impossible» to distinguish some tones. “I had to innovate in places since there was nothing else,” he explains. “I modify these paintings, I bring them up to date,” he told our colleagues from France 3 last week. The local regional press has been following the case since the beginning. In an article signed in person by Patrick Quercy, local journalist for the title, the Journal of Haute-Marne reports the discovery of the paintings from July 2021. Then, in September, The Voice of Haute-Marne published a story that praised the initial renovations.

The samurai at the Musée Guimet take off their masks.

The neighborhood is thereafter filled with admiration. “The neighbors who saw the deteriorated paintings and then the repaired ones were shocked, amazed,” recalls Patrick Quercy, who bears responsibility for the changes and is pleased with his work “given the original state of the canvases.” «Of course, the experts will disagree, but the general public had an unexpectedly good reaction: they all thought the job was great,” he claims. Throughout the fall and winter, the campaign to restore the fourteen paintings continued. Only two and a half canvases were still intact on Monday.

A set slipped by unnoticed.

The discovery and restoration of the paintings are ultimately brought to the attention of the Grand-Est region’s Regional Directorate of Cultural Affairs (Drac) in March. It’s been eight months. The matter had not been brought to the attention of the service, neither by the town hall nor, even more so, by the clergy. When told what was in the Saint-Brice de Chatonrupt church last summer, the young local priest, who was “totally overburdened” and in charge of 59 locations, would have been pleased to notify out that the goods belonged to the municipality, according to the mayor. The fortuitous discovery of the paintings should have been the subject of a report from the town hall to the prefect, who would then have contacted the competent services, according to the heritage code.

Given their state, I had no illusions that we would have been escorted.

Mayor of Chatonrupt-Sommermont, Joel Agnus

When contacted by the Drac Grand Est at the end of March, the mayor of Chatonrupt-Sommermont told the Figaro that the restorations were being halted. His phone has been calling more frequently than normal since then. Interlocutors describe a “massacre” artwork, much to his amazement. Jol Agnus expresses his displeasure with the situation. “Given their condition, I couldn’t suppose we could have been accompanied in the least.” “I don’t know anything about restaurants,” the mayor admitted. He believes he was not given enough information on what he should have done. “In the thirty years that I’ve been mayor, I’ve never had to think about these issues,” he says, noting that Chatonrupt-Sommermont, which has a population of about 300 people, has no classified properties or historical monuments.

Read alsoThe Albert-Kahn Museum’s Revival: Opening Up to Others and the World

Patrick Quercy, the restorer of the Stations of the Cross, is likewise taken aback by the current uproar caused by his labor. “This type of local repair by volunteers is extremely typical, he assures. That sort of thing happens all the time. This identical type of item is routinely stolen in other municipalities and ends up at flea markets. Patrick Quercy only recently learned of a cultural inventory conducted in Chatonrupt-Sommermont in 2006. The paintings had been unnoticed since then. Similarly, the multiple echoes of the discovery published in the local news, such as the permanence of Joinville, five kilometers from town, did not elicit a response from the Drac Grand Est referents. “”There appear to have been misunderstandings and failures at every level,” Jol Agnus argues. When contacted by Le Figaro, Drac Grand Est declined to comment “before to the expiration of the electoral reserve period.”

“We acted in good faith, seeking to preserve what had been fortuitously discovered, even if it was not done in the most efficient manner possible, explains Chatonrupt-mayor. Sommermont’s Otherwise, we would not have restored these canvases since it would have cost the municipality too much.” Despite the fact that the reversibility of restorations appears to be a source of concern for Drac specialists, Patrick Quercy intends to finish his repair of the twelfth table. “Half of it is already gone; it would be foolish to leave it that way.” Especially because, following the Behold the Man of Zaragoza and St. George’s of Navarre, France may have a position in the ballet of dangerous restorations.