What an epic Juanillo has lived. And what a hero he is made. He single-handedly defeated an enemy offensive. He has risked his life to capture a flag. He has even been able to handle a Russian tank. But nothing as extraordinary as the visit he receives when, to recover from his injuries, he rests in a hospital. “Suddenly an idea arises in his brain… Could he be […] the great Caudillo who leads the troops to victory? Adventures of Juanillo, which Carmen Martel conceived in the middle of the war, but published in 1941. Who knows how many children were infected by that emotion and bravery. That’s why, after all, that story was written. And, in general, the majority of those were published at that time, according to research Children’s and youth literature in the Civil War, by Professor Jaime García Padrino (Renaissance). In a country that was throwing bullets and bombs at each other, he maintains that fables also entered into combat.

Good dukes who shoot sweets on their neighbors, in the face of implacable dictators. Reds eager to “machine-gun priests, women and the elderly.” Police officers so cruel as to even arrest the Moon, suspected of complicity with the people. “Literature for the little ones was used as a weapon, in an ideological confrontation between two ways of seeing the world,” says García Padrino. “It was turned into another manipulative element in the hands of both sides. […] The literary justification was relegated to a mere vehicle for instructive content,” the book reads.

The conclusion is based on four decades of study. And it is now summarized in 260 pages, the closing of a trilogy with which the professor has analyzed children’s and young people’s books from 1875 to 2015. The oldest and most recent installments have already been published. Perhaps the most complex was missing, the ring of conjunction, the years that divided Spain in two. Although García Padrino comments that the different publication rates are his own thing, not political rejections from some label.

Another premise also becomes clear immediately: “My purpose has always been the most total objectivity. “Base myself on books, magazines, documents.” In the republican rewriting of a Cinderella who decides not to marry “any prince or any character from a privileged class”; in the ugly duckling that becomes a swan “dedicated to the education of the people”; or, on the contrary, in Miguelillo, protagonist of The treasure of Texihualpa, by Emilia Cotarelo, dedicated to conquest, God and piety; or in The story of El Caudillo, the savior of Spainwhose title suggests the content of its pages: “Franco was not only the Chief of unsurpassed personal courage, who despised risk and never lost his serenity, but he was also the loving father to his soldiers.”

García Padrino’s approach avoids political or ethical assessments and focuses on the collection of facts. He cites the proclamations that included another work with an emblematic name, A ten-year-old hero or ¡Arriba España! by Manuel Barberán Castillo: “The anarchists wanted to destroy everything. The communists wanted to steal everything, and all the Marxists wanted to seize what was not theirs. They only thought about living like beasts. “They were always drunk and committed all kinds of excesses that the children imitated.” And, on the other hand, it recovers the discovery of the Spanish Pinocchio in The war of the dolls, by Magda Donato and Salvador Bartolozzi: “The ‘expensive’ dolls lived in nice little houses […] The ‘cheap’ ones lived poorly, crammed into dozens of boxes. […] Sorry to disappoint you, but the expensive ones […] Not only did they not console them or pity them, but they hated and despised them… for being poor and unfortunate! What strange things happen between dolls, right?”

Based on examples, the professor regrets, incidentally, that the war interrupted the 1930s that had shown great creativity in children’s books. From talent and genius, he considers that he went to propaganda. Some against “the bad reds”. Others to attack the “terrible fascists.” At the antipodes of thought and the trenches. But united by a similar desire for proselytism. And because of the importance they gave to conquering the most defenseless minds.

“There are no more ogres, nor almost chained princesses to free. But there are other ferocious monsters such as the exploiter without conscience, the chief, the tyrant, who have enslaved by violence the purest and noblest beings in society. And children had to be warned against those monsters,” the book explains the words of Ramón Puyol, painter and artistic director of the Altavoz del Frente organization. Just as the nationals stressed the “advisability of giving preferential attention to the little ones and the need to sow in their souls, and with fair measure, the idea of Homeland, of love for the Leader, of obedience, of discipline, of admiration.”

Hence, the authors found themselves at a crossroads. García Padrino believes that many put their stories at the service of their political faith. “Few reported what was happening and others left it alone. There was an obvious impoverishment of children’s publications during the war,” he adds. And, as an exception, the quality of Err Asan (Josep Serra Masana) stands out, who insisted on remaining faithful above all to literature in works such as The eight suitors o The house of the seven maidens.

EFE

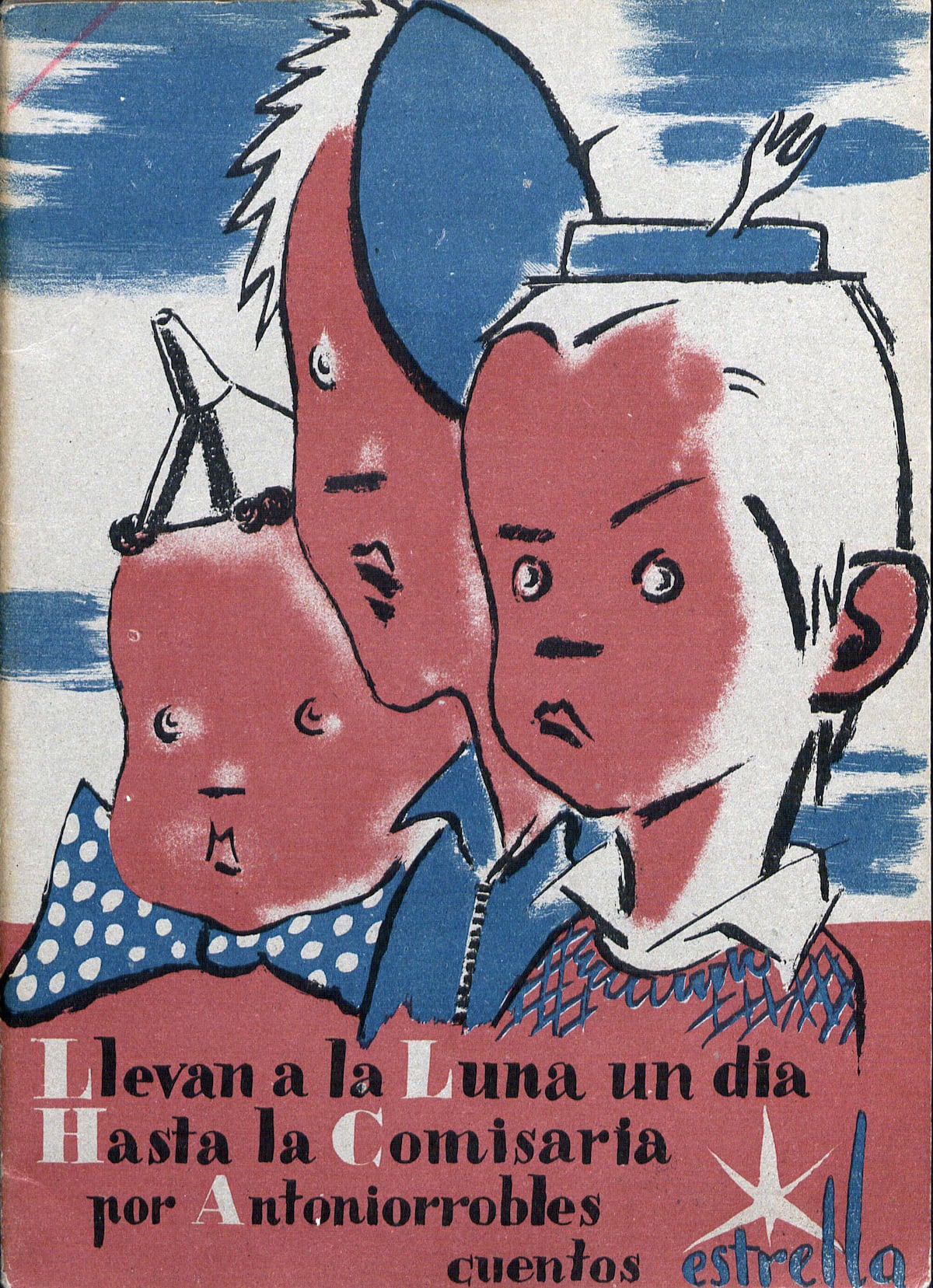

On the contrary, the book abounds with more dubious examples. García Padrino highlights obvious things, forced poetic images or crude attempts at persuasion. In Flechín and Pelayín in the bandits’ cave, with texts by J. Aguilar de Serra, it read: “The reds raised their fists with hatred. The white people extended their hands with love.” On the opposite front, many pages of the book are dedicated to Antoniorrobles, “a classic and great innovator of Spanish children’s literature who, at the time of the war, took the Republican side,” according to García Padrino. Through the adventures of Sidrín or Botón Rompetacones, the writer transmitted clear messages: “Perfumito had a very ugly habit; paint with charcoal or chalk […] the swastika: that unfriendly cross or sign, which looks like the arms and legs of a crazy and stupid dancer.” Or the description, in Don Nubarrón in the shelters, of the eponymous character: “He was a fat, mustachioed man, who ate good chops, smoked good cigars and used a ball cane. He was a terrible fascist, what he wanted was for the working class to always continue working for the rich.”

Between one side and the other, García Padrino recognizes Elena Fortún’s effort to denounce the horrors, inequalities and unjust suffering of children. In The two brothers, “Everything changed so much that within a few days [Juanín y Carmelina] They had no father, no mother, no house, no chacha, not even a cat.”

And in The city of starsicons of fables question a child who has recently arrived in the city from the country of scary stories.

“You will know what has become of my grandmother,” insisted Little Red Riding Hood.

― […] When the war started they burned her house and she left along the roads with other old women who were also leaving.

– And our parents? ―asked Thumbelina.

― They insisted that they wanted to eat every day, and they got very angry. Then, to silence them, they killed them with a bomb.

“How horrible,” cried Little Red Riding Hood, “that story is horrible, much worse than the one about the wolf.”

On that, at least, everyone can agree.