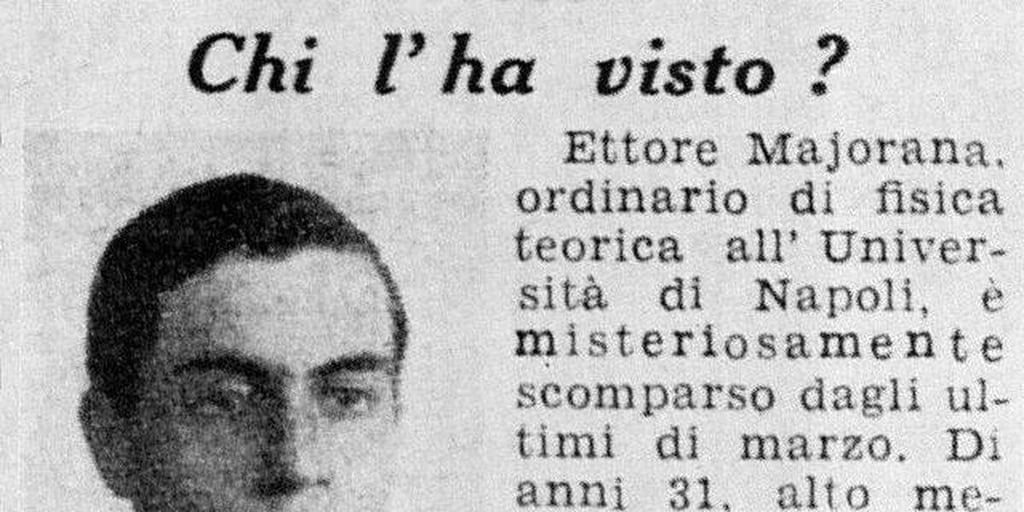

«I only ask one thing of you: do not wear black, and, if it is to follow custom, only wear some sign of mourning, but not for more than three days. Then, if you can, remember me with your heart and forgive me. This brief letter written by the physicist Ettore Majorana was left on March 26, 1938 in his room at the Hotel Boloña, in Palermo. It was not the only letter he left: a telegram arrived those fateful days to Antonio Carrelli, the director of the Physics Institute of the University of Naples, where Ettore had just obtained a position as a professor to teach classes. “I have made an inevitable decision,” it read. There is no selfishness in her. But I know that my unexpected disappearance will be an inconvenience to you and the students. I ask you to forgive me, more than anything for having put aside the trust, sincere friendship and generosity that you showed me.”

It would not be the last that Carrelli would receive. A second letter, also sent from Palermo, seemed to contradict the previous one or, at least, show that Majorana’s idea had changed. «Dear Carrelli, the sea rejected me without remedy. I will return tomorrow to the Hotel Boloña. But I decided to leave teaching. I will be at his disposal to give him more details. However, Majorana, one of the most important scientists of his time, compared to Newton or Galileo, was never heard from again.

More than eighty years have passed, and the mystery continues. Since then, hypotheses have followed one another: did he commit suicide tormented by what his scientific findings could mean for the world? Did he take a boat and flee his life to another continent? Did he seclude himself in a monastery in southern Italy? Did he end up begging and helping kids with his math and physics homework? The answer, like the ‘domestication’ of the particle that bears his name and which is both matter and antimatter (and which could be key to the development of quantum computers), remains a pending task.

A private life

Majorana was born in Catania (Sicily) on August 5, 1905 into a wealthy family. Since he was little, he showed signs of having a singular intellect, with a privileged mind for mathematics, although with a sullen personality that did not make him have many friends. He began studying Engineering in Rome, but soon left it for Physics after arriving in 1928 at the institute directed by Enrico Fermi, an eminence at the time, but who would be recognized worldwide years later for developing the first nuclear reactor, being considered as ‘ the architect of the atomic bomb’ (not in vain was he one of the main leaders of the Manhattan Project).

But long before this, Fermi as Majorana’s mentor and other young people such as Bruno Pontecorvo, Franco Rasetti or Emilio Segrè (the latter, a friend of Majorana and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1959 for his discovery of the antiproton), were exploring physics. nuclear and particle. From here, his fame among the scientific community grew, especially as a result of prophesying the existence of the neutron (the ‘glue’ of the atom) and, later, that of the particle that bears his name and which is both matter and antimatter, prone to self-destruction.

But Majorana had an atypical relationship with his scientific work: in his entire life, he only published a dozen studies – the last one came to light after he had already disappeared – since he considered that when he solved an enigma, it, no matter how complicated it was, been to solve, he lost his interest. He also worked with personalities of the stature of Werner Heisenberg (pioneer of quantum mechanics and Nobel Prize in Physics in 1932 for his discoveries in this regard) and Niels Bohr (Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922 and considered the only person who proved that Einstein was wrong about something. ).

«There are several types of scientists. There are those of the second and third order, who do their job correctly. There are those of the first order, who make discoveries that contribute to the progress of science. And then there are geniuses like Galileo or Newton. Well, Ettore Majorana was one of them,” Fermi himself said about him – according to the book ‘The Disappearance of Majorana’ (Tusquets Editores, 2023), by Leonardo Sciascia, whom many consider less brilliant than the Sicilian physicist. although he was more charismatic, which made his name more familiar to us today.

Hypotheses about their destiny

But Majorana’s bright future came to a sudden halt in 1938, after the week before his disappearance he withdrew a large sum of money from the bank, bought a ticket to Naples and headed to the port of Palermo with his passport. There he loses track of him forever.

In the following years, alleged Majorana sightings multiplied. Witnesses claimed that they saw him begging in Naples, turned into a person they called ‘dog-man’ and who helped local young people with their math homework; They also asserted that they knew him as a monk in a monastery in Calabria; several testimonies were located in different countries in South America…

The least far-fetched hypothesis may have been suicide. But his family maintained that it was impossible, since he was a devout Catholic. In fact, his mother even wrote a letter to Mussolini to help her look for him. Sciascia and other authors claim that, as a ‘visionary’ of his time and sensing what his research could mean for future nuclear weapons, he disappeared from the map.

And the mystery has even reached the new millennium. In 2011, Rome prosecutors reopened their investigation into his disappearance. Detectives had found an alleged photograph of Majorana from 1955 in Venezuela, where he allegedly lived under the alias ‘Mr. Bini’. By comparing the facial structure of the image with another old photo of the physicist, they concluded that it was the same person. The case was closed definitively in 2015.

But many were dissatisfied. Francesco Guerra, a physicist at the Sapienza University of Rome who continues to investigate the event, says the conclusion was “completely ridiculous.” He, together with Nadia Robotti, a physics historian at the University of Genoa, have another hypothesis that they published in 2013 in the journal ‘Physics in Perspective’: Majorana died approximately a year after disappearing. And they say they have proof, as a letter written by a Jesuit priest to Majorana’s brother in 1939 pays tribute to the “lamented Ettore Majorana” and the “dearly beloved.”

Guerra and Robotti still don’t know where or how he died, but they believe his descendants have documents that would shed more light. And three years ago, researchers flew to UC Berkeley to visit the archive of Emilio Segrè, whose friendship with Majorana soured in the years before he disappeared. There they found a folder that, according to Segrè’s instructions, cannot be opened until the year 2057. Guerra hopes it contains details that will solve the case once and for all.

The search for the Majorana quasiparticle follows a similar dynamic: at first, many researchers strove to domesticate this particle that resembles the future of its discoverer: despite being tremendously promising, no one knows for sure what happens to it.