My favorite example to illustrate the relationship between technological innovation and defense is not a weapons system: it is a piano manufactured since 1942 by the prestigious firm Steinway & Sons for the American army. With three peculiarities: it is camouflage green, it is built with metal and it was designed to be dropped by parachute on the European front. On the cold winter nights of 1945, some American battalion celebrated its advance towards Berlin to the rhythm of Gershwin.

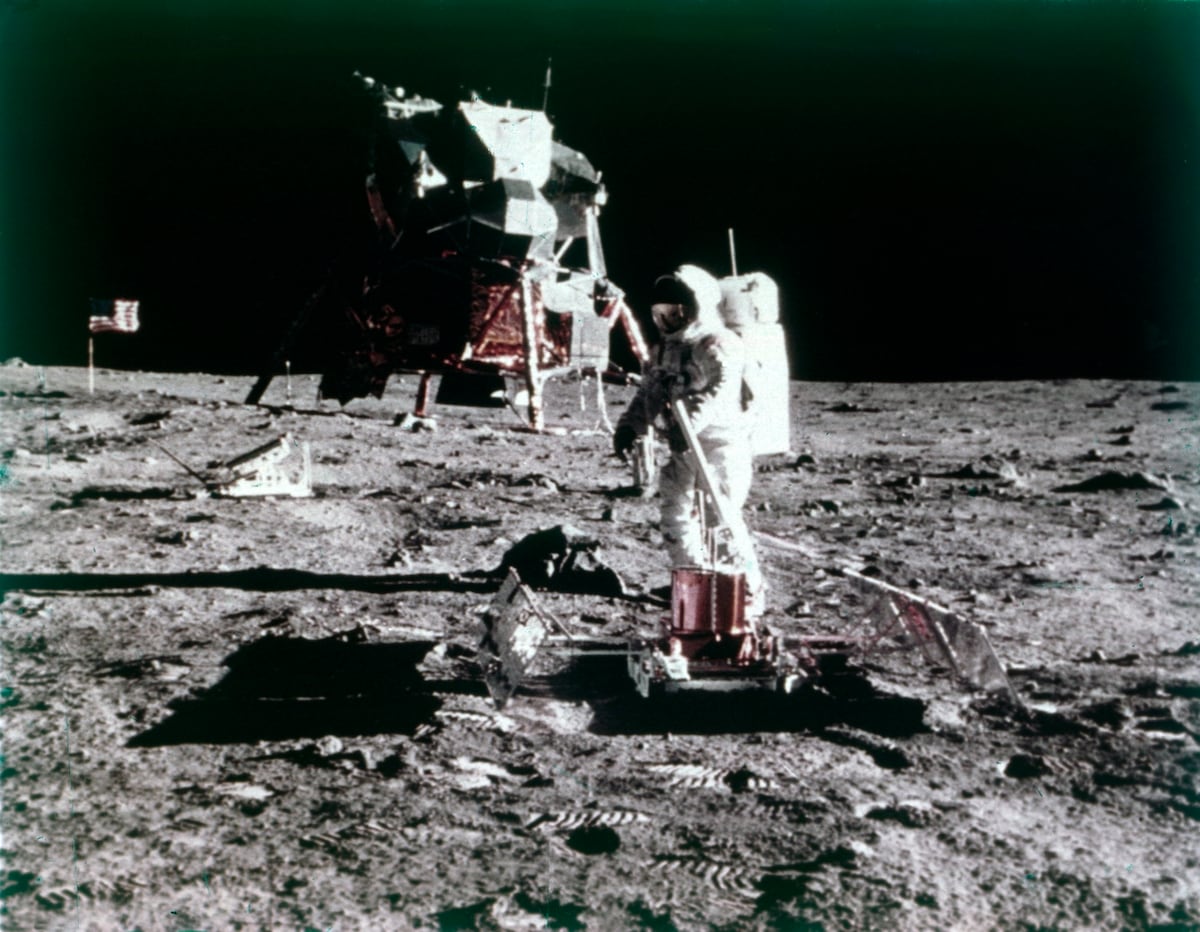

Wars have been, for as long as we have records, powerful sources of technological innovation. Radar and penicillin, developed in World War II, gave way to nuclear energy and space technologies during the Cold War – the space race, marked by the victory of the Apollo 11 program, was just another form of conflict between the United States and the USSR―. So Steinway’s Victory Vertical pianos may seem like an anecdote, but they reflect the ability of a war economy to develop innovative solutions to unmet needs. And they are also an excuse to face a crucial debate in a polarized world: that of European strategic autonomy in critical technologies, that is, that of technological sovereignty. A debate fueled by European dependence on supplies and energy, so evident with the Covid-19 crisis and the conflict in Ukraine, and increasingly necessary in the face of the growing technological rivalry between China and the United States.

The EU has been betting on a challenge-oriented R&D policy for fifteen years and proposing innovation missions for six. With uneven results, perhaps because the inspiring model of these missions – precisely the Apollo 11 program – did not fit in the peaceful Europe of 2018. It is not necessary to be at war for an innovation mission to bear fruit, but it is necessary to share a sense of urgency . Scientific success against the pandemic reminds us that targeted R&D works best when we face an existential challenge – a being or not to be – and that, in the end, it generates dividends. It is enough to contemplate how messenger RNA technologies illuminate new gene therapies to understand that innovation missions produce spillovers: applications with interest beyond the initial objective. The next time you reach for an energy bar, remember that you owe it to the Apollo program.

Understand me. I do not want to say that the five European innovation missions, which have generated numerous replicas in the Member States, are not urgent. Decarbonizing one hundred European cities or restoring the oceans by 2030 is essential, but it mobilizes less will and resources than an immediate existential challenge. Because that’s what we’re talking about. As High Commissioner Josep Borrell often repeats: Europe is in danger. We face a hostile scenario in which security increasingly occupies the agenda of political leaders and, for the first time, technological sovereignty begins to move to the center of the debate, with the tailwind of the new European industrial policy. A shared vision emerges that deep technologies, deep techare not only a promise of economic prosperity, but a key to our security.

This end of the European mandate is forging an agreement to invest in critical deep tech, starting from the identification of those in which the EU should have its own leadership. We talk, among others, about quantum technologies, biotechnologies, semiconductors and, of course, artificial intelligence. As a first step, in February an agreement was reached to launch the Strategic Technologies Platform for Europe (STEP), which will mobilize various community funds to promote projects that will have a seal of sovereignty.

Other European countries have already launched their own strategies deep tech, often embedded in broader innovation or entrepreneurship policies. That is why the announcement by the Minister of Science, Innovation and Universities, at the beginning of the legislature, that Spain will have its own strategy for the development of the deep tech. A strategy that should identify national leaders, align instruments that already exist in our R&D&I policy and, without a doubt, deploy others that allow the most promising projects to reach the market faster.

It will not be easy, as a recent forum organized by Retina and Transfer recalled. Generating own leadership in disruptive technologies is never, as specialized investors who operate with high risk-high reward logic know. Recognizing our progress in recent years, from the culture of academic-business collaboration to the maturity of specialized venture capital, is a good start. Remembering the transformative power of public investment, directed at shared challenges and guided by a sense of urgency, is another key. No one knows for sure which tune will end up triumphing in the technologies most critical to European security, but we shouldn’t let anyone play it for us.