Aletta Jacobs (February 9, 1854 – August 10, 1929) was a physician, feminist pioneer, and one of the most influential people of the twentieth century. Although she lived most of her life during the Victorian era, she was one of the women who left a great impact, as the first woman to attend and graduate from the University of Amsterdam. In 1878, she obtained her doctorate only one year later. Thus, she was the first woman to attend a Dutch university, the first woman to obtain a medical degree in the country, and the first woman to obtain a doctorate in medicine.

Jacobs subsequently managed to combine professional life, marriage, and political activity, and founded what may be considered the first birth control clinic. She also led campaigns for women’s liberation, for women’s working conditions, and for the introduction of women’s suffrage in the Netherlands. She was a prominent leader in both organizations. International, Dutch and in the women’s peace movement during World War I.

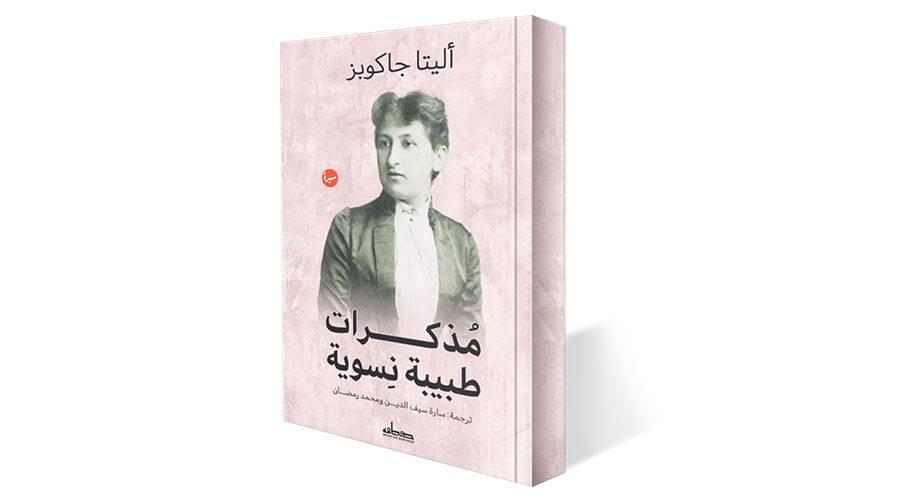

Everything we know about Aletta Jacobs about her life and work depends on what she chose to tell us in her memoirs, an Arabic translation of which was issued by Safsafa Publishing and Distribution House, completed by Sarah Seif El-Din and Mohamed Ramadan, under the title “Memoirs of a Feminist Doctor.”

Jacobs was an extraordinary person, but she was not alone in her struggle. She was fortunate to live at a time when new options and opportunities became available to women. She was part of the first generation of female doctors and European feminists who helped open educational and professional doors for themselves and others.

Jacobs defied many of the prevailing norms of her time, and refused to live the life of a traditional Victorian woman. Middle-class girls in the mid-nineteenth century were expected to remain within the confines of the home, as wives and mothers, but Jacobs rebelled by following in her mother’s footsteps as a housewife. Girls’ education was Segregated except at the elementary level, Jacobs strongly advocated co-educational education for men and women.

Jacobs hated attending girls’ schools, and was not at all interested in learning etiquette and housekeeping skills. She decided to study medicine instead. She helped pave the way for women to become doctors and continued to practice medicine even after her marriage, even though it was not appropriate for a married woman of the class. The middle position is to work outside the home unless that work is voluntary.

Aletta Jacobs was not a revolutionary, nor did she want to be, but her views and personal behavior were far ahead of her time. In the late 19th century, respectable women were not supposed to walk the banks of canals in the winter, or walk on some of the main roads in the post-19th century. Noon, not to mention appearing in public places without an escort or walking alone after dark, because respectable women at that time had to have a husband who took care of their interests so that she could stay at home.

However, Jacobs enjoyed walking these roads, insisted on visiting her patients and family day or night, on foot, attended theatrical performances, and participated in political meetings as a single woman, before the end of the nineteenth century.

By the time of her death in 1929 at the age of seventy-five, Jacobs’s sophisticated views and lifestyle had drawn far fewer objections than during her younger years.